Key Takeaways

Complete history of Russ Houk's legendary wrestling camp at Maple Lake, Pennsylvania (1962-1976). Learn how this pioneering program became the U.S. Olympic Training Center and shaped American wrestling excellence through generations of champions.

The Visionary: Russ Houk’s Wrestling Background

Understanding the camp’s extraordinary success requires examining the remarkable career of its founder, whose wrestling expertise and coaching philosophy shaped American wrestling during a transformative era.

Early Wrestling Career and Coaching Foundation

Russell “Russ” Houk developed his wrestling foundation during the 1940s and 1950s when the sport was transitioning from informal competition to structured collegiate programs. His competitive experience provided firsthand understanding of training needs that would later inform his revolutionary camp approach. Unlike many wrestling coaches of his era who relied primarily on toughness and repetition, Houk studied technique systematically, analyzing movements biomechanically and developing progressive training sequences that built skills methodically rather than through trial and error alone.

Houk’s coaching philosophy emphasized several principles that were revolutionary for his time, including technical precision over brute strength, systematic skill progression from fundamental to advanced techniques, mental preparation alongside physical conditioning, individual attention within team training environments, and continuous learning from both victories and defeats. These principles would distinguish both his collegiate coaching career and his camp programs, creating comprehensive wrestler development rather than simply teaching moves.

Bloomsburg State College Coaching Excellence

In 1957, Russ Houk was hired as head wrestling coach at Bloomsburg State College (now Bloomsburg University), beginning a 14-year coaching career that would establish him as one of the most successful coaches in collegiate wrestling. During his tenure from 1957 to 1971, Houk’s teams compiled a remarkable 142-34-4 record, achieving a winning percentage exceeding 80% while competing against increasingly sophisticated programs as collegiate wrestling expanded nationally.

Houk’s Bloomsburg teams captured five Pennsylvania State Collegiate Athletic Conference (PSCAC) championships, demonstrating consistent conference dominance throughout his tenure. More impressively, his teams won three National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) national championships, establishing Bloomsburg as a national wrestling power despite competing as a smaller state college against larger institutions with more resources. These championship teams featured wrestlers who would later attend Houk’s summer camps as instructors, creating a virtuous cycle where successful collegiate wrestlers returned to teach younger generations.

Houk’s coaching success stemmed from meticulous preparation, innovative training techniques, and an ability to maximize each wrestler’s potential regardless of physical attributes. He developed wrestlers who competed effectively against physically larger opponents by emphasizing technique, positioning, and strategic thinking over pure athleticism. This approach proved particularly effective at the NAIA level, where athletic talent varied more widely than in larger NCAA Division I programs, requiring coaches to develop technical sophistication that could overcome athletic disadvantages.

Olympic Wrestling Committee Leadership

Houk’s expertise earned recognition beyond collegiate coaching when he was appointed to the United States Olympic Wrestling Committee in 1964, serving continuously through 1976 during one of the most successful periods in American wrestling history. His committee responsibilities included selecting Olympic team members, developing training protocols, coordinating international competition preparation, and serving as team manager for freestyle wrestling teams.

Houk served as manager for the United States freestyle wrestling teams at both the 1972 Munich Olympics and the 1976 Montreal Olympics, positions of enormous responsibility during Cold War era competitions where wrestling served as ideological battleground between Western and Soviet bloc nations. American wrestling success during this period owed significantly to preparation systems Houk helped develop and implement, combining technical refinement, physical conditioning, mental preparation, and international competition experience.

His Olympic committee involvement provided unique insights into elite-level training requirements, exposing him to international coaching methodologies from Soviet, Iranian, Turkish, and other wrestling powers. Houk synthesized these diverse approaches with American wrestling traditions, creating hybrid training systems that leveraged the best techniques regardless of origin—an innovative approach when Cold War politics often prevented such cross-pollination of coaching philosophies.

Founding the Camp: Vision and Early Years (1962-1964)

The establishment of Russ Houk’s wrestling camp in 1962 represented a pioneering effort that would transform American wrestling training and establish a model followed by countless camps subsequently.

The 1962 Launch at Maple Lake

In 1962, Houk launched his wrestling camp at Maple Lake in Forksville, Pennsylvania, a rural location in Sullivan County approximately 30 miles northwest of Bloomsburg. The site offered several advantages for intensive wrestling training, including geographic isolation minimizing distractions, natural recreational facilities supporting team building, affordable accommodation for extended training periods, and proximity to Bloomsburg allowing Houk to leverage his collegiate connections.

The initial camp structure featured intensive multi-day training sessions unlike the single-day clinics common in early 1960s wrestling. Wrestlers attended for one or two weeks, immersing themselves completely in wrestling technique, conditioning, and competition without the distractions of home environments. This immersive model proved revolutionary, allowing skill development that was impossible through periodic practice sessions during regular seasons.

Houk’s inaugural camp attracted wrestlers primarily from Pennsylvania and surrounding states, with attendance ranging from youth competitors to high school wrestlers preparing for collegiate competition. The program combined technical instruction in fundamental and advanced moves, intensive drilling to develop muscle memory, live wrestling against varied opponents, conditioning work building wrestling-specific fitness, and educational sessions on nutrition, weight management, and mental preparation.

Innovative Training Methodologies

What distinguished Houk’s camp from earlier wrestling instruction was its systematic, progressive approach to skill development. Rather than simply demonstrating moves and having wrestlers practice them, Houk developed structured progressions that built complex techniques from fundamental components. Wrestlers learned not just what to do but why specific techniques worked, understanding the biomechanical and strategic principles underlying effective wrestling.

The camp incorporated several innovative elements that would become standard in wrestling camps subsequently, including position-specific training focusing on particular situations like escapes, takedowns, or pinning combinations, video analysis examining both wrestlers’ own performances and elite competitors’ techniques (revolutionary when video equipment was expensive and rare), round-robin tournaments providing competition against varied opponents and styles, weight management education teaching healthy approaches rather than dangerous crash dieting, and mental training techniques borrowed from emerging sports psychology research.

Houk’s coaching staff consisted primarily of his successful Bloomsburg wrestlers, creating a unique environment where relatively young instructors who had recently competed could relate to campers while demonstrating techniques at high levels. This peer-teaching model proved particularly effective for high school wrestlers who responded better to instruction from recent high school graduates and young college wrestlers than from older coaches perceived as disconnected from current competition.

Building Reputation and Expanding Reach

The camp’s quality quickly built a strong reputation within wrestling communities. Wrestlers who attended returned markedly improved, demonstrating refined technique and enhanced conditioning that translated into competitive success. Word-of-mouth recommendations from satisfied participants and their coaches drove steady enrollment growth, expanding the camp’s geographic reach beyond Pennsylvania to include wrestlers from throughout the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions.

By its third year of operation, Houk’s camp had established itself as one of the premier wrestling training facilities in the eastern United States, attracting attention from USA Wrestling (then the United States Wrestling Federation) and Olympic committee members seeking training venues for national teams. This reputation would soon elevate the camp from regional training facility to national wrestling institution.

The Olympic Era: 1964-1973

The camp’s designation as the U.S. Olympic and Pan-American Games Training Camp transformed it from successful regional program to internationally significant training facility that would shape American wrestling during its most successful Olympic period.

Becoming the Official Olympic Training Center

In 1964, USA Wrestling designated Maple Lake as an official training center for Olympic and Pan-American Games preparation, marking extraordinary recognition for a facility that had operated for only two years. This designation reflected both the camp’s proven training effectiveness and Houk’s growing influence within national wrestling leadership through his Olympic committee involvement.

The Olympic designation brought several significant changes to camp operations, including extended training periods accommodating national team preparation schedules, enhanced facilities and equipment meeting international training standards, expanded coaching staff incorporating national team coaches and international technical experts, increased funding from USA Wrestling and Olympic committee resources, and intensified competition as Olympic hopefuls sought admission to these elite training sessions.

From 1964 through 1973, Maple Lake hosted numerous Olympic team training camps, Pan-American Games preparation sessions, and international competition training as American wrestlers prepared for tournaments worldwide. The facility became a pilgrimage site for serious American wrestlers, where spending a summer training meant access to the nation’s best competitors, most knowledgeable coaches, and most intensive preparation available domestically.

The camp also hosted Canadian national teams preparing for World Championships and Olympic Games from 1968 through the early 1970s, creating unique international training environments where American and Canadian wrestlers trained together, sharing techniques and pushing each other to higher performance levels. These international partnerships were unusual during the Cold War era when political tensions often prevented such collaborative training arrangements.

Legendary Wrestlers and Olympic Champions

The roster of elite wrestlers who trained at Maple Lake during the Olympic era reads like a wrestling hall of fame, representing the greatest generation of American wrestlers and including numerous Olympic medalists, world champions, and NCAA titlists.

Dan Gable trained at Maple Lake during his competitive career before becoming arguably the most famous American wrestler in history. Gable’s 1972 Olympic gold medal in Munich (won without surrendering a single point throughout the tournament) came after preparation that included Maple Lake training camps where he refined technique and sharpened conditioning against America’s best competition. Gable would later establish his own legendary coaching career at the University of Iowa, but his competitive foundation was built partly through Houk’s training methodologies.

Chris Taylor, the 1972 Olympic bronze medalist in super heavyweight freestyle wrestling, trained extensively at Maple Lake despite his exceptional size (over 400 pounds). Taylor’s success demonstrated Houk’s training philosophy’s effectiveness across all weight classes, as the technical precision and conditioning work developed at camp translated effectively even for the sport’s largest competitors. Taylor’s bronze medal represented American super heavyweight wrestling’s resurgence after years of Soviet and European dominance at the heaviest weights.

John Peterson and Ben Peterson, brothers who both won Olympic medals in 1972 (Ben gold, John silver) trained together at Maple Lake, developing the complementary styles that made them two of the most successful American wrestlers of their generation. Ben Peterson would add a second Olympic medal (silver) in 1976, while John became a national team coach, continuing the cycle of Maple Lake-trained wrestlers returning as instructors.

Wade Schalles, who holds NCAA records for most pins and most career wins, was a regular Maple Lake attendee who developed his aggressive, offense-oriented style through training that emphasized attacking wrestling rather than defensive positioning. Schalles would become one of the most successful collegiate wrestlers in history at Clarion University, winning three NCAA championships while demonstrating the attacking philosophy Houk encouraged.

Wayne Wells won Olympic gold in 1972 at 163 pounds, demonstrating technical mastery and strategic wrestling developed through years including Maple Lake training. Wells’ Olympic success showcased how smaller, technically sophisticated wrestlers could compete effectively against physically stronger international opponents when proper training built skill foundations capable of overcoming raw athleticism.

Stan Dziedzic captured Olympic gold in 1976 at 149.5 pounds, representing the continued success of Maple Lake-trained wrestlers throughout the 1970s. Dziedzic’s victory came at the Montreal Olympics, Houk’s final Olympics as team manager, creating a fitting culmination to the Olympic era of Maple Lake’s influence on American wrestling.

Other notable wrestlers who trained at Maple Lake included Rich Sanders, Gray Simons, Don Behm, and numerous NCAA All-Americans and national champions who went on to successful coaching careers themselves, spreading Houk’s training philosophies to programs nationwide.

Training Methods and Olympic Preparation

The Olympic-era training at Maple Lake combined traditional American wrestling fundamentals with emerging sports science, international techniques, and innovative preparation methods that were revolutionary for the 1960s and early 1970s.

Training sessions followed carefully structured daily schedules that balanced intensive workouts with adequate recovery, addressing the overtraining problems that plagued many wrestling programs of that era. Typical training days included morning technique sessions focusing on specific positions or situations, afternoon live wrestling providing competition against varied opponents, evening video review analyzing both personal performance and international competition footage, supplementary conditioning work building wrestling-specific fitness, and educational sessions covering nutrition, sports psychology, and injury prevention.

The camp incorporated international techniques that Houk observed through Olympic committee work, synthesizing Soviet chain wrestling sequences, Iranian body lock variations, Turkish gut wrench methodologies, and Eastern European par terre (ground wrestling) approaches with traditional American folkstyle foundations. This technical eclecticism gave American wrestlers broader technical repertoires than competitors from nations with more rigid stylistic traditions, creating tactical advantages in international competition.

Houk’s camp pioneered systematic weight management education at a time when dangerous cutting practices were common and often encouraged. Understanding that unsafe weight loss compromised both health and performance, camp programs taught proper nutrition, gradual weight reduction, and maintaining competitive weight year-round rather than through dramatic pre-competition cutting. This progressive approach prevented the health problems that affected many wrestlers of that era while ensuring peak performance at competition time.

Mental preparation received unusual emphasis for that period, with camp sessions addressing competition anxiety, visualization techniques, strategic thinking under pressure, and maintaining composure when trailing in matches. Houk recognized that technical skill and physical conditioning meant little if wrestlers couldn’t execute under Olympic-level pressure, so camp training simulated high-pressure situations preparing wrestlers psychologically for championship competitions.

Legacy and Influence on American Wrestling

Russ Houk’s wrestling camp influenced American wrestling far beyond the champions it produced, establishing training philosophies, program structures, and competitive approaches that shaped the sport for decades.

Pioneering the Wrestling Camp Model

Houk’s camp pioneered the intensive, multi-day wrestling camp model that became standard throughout American wrestling. Before Maple Lake demonstrated its effectiveness, wrestling instruction occurred primarily through regular season practices and occasional single-day clinics offering limited depth. The immersive camp model proved dramatically more effective for skill development, creating a template subsequently adopted by college programs, state wrestling associations, and private wrestling enterprises nationwide.

The key innovations Houk’s camp model introduced that became standard elements of wrestling camps include extended duration allowing sustained focus rather than brief instruction, residential format minimizing distractions and building team cohesion, progressive skill sequences developing techniques systematically, competitive elements providing practice opponents, comprehensive programming addressing technique, conditioning, and mental preparation, and qualified instruction from successful wrestlers and experienced coaches. These elements appear in virtually every serious wrestling camp today, demonstrating Maple Lake’s lasting structural influence.

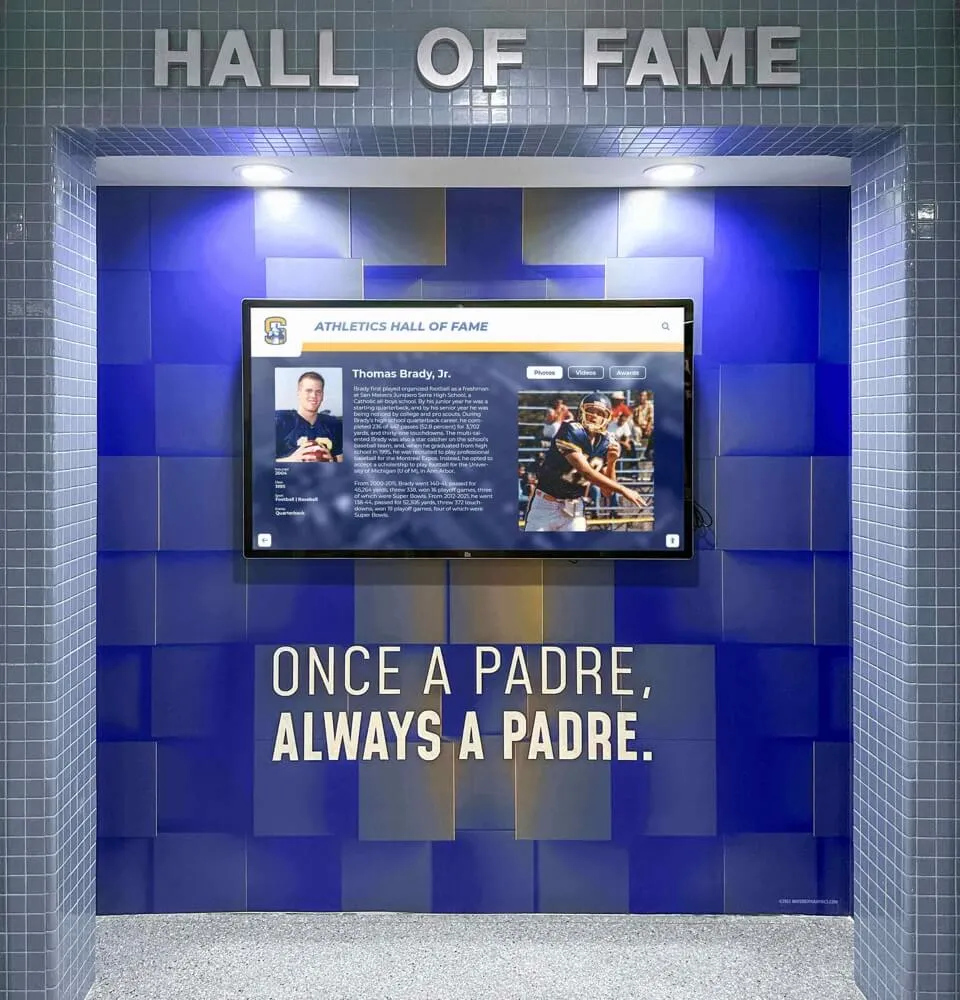

Schools and programs seeking to recognize their wrestling heritage should explore how state championship displays can honor not just individual champions but also training traditions and coaching legacies that built successful programs over generations.

Coaching Tree and Spreading Methodologies

Perhaps Houk’s greatest legacy came through the wrestlers and coaches trained at Maple Lake who subsequently established their own programs, spreading his training philosophies across American wrestling. Dan Gable’s legendary Iowa program, which dominated NCAA wrestling for decades, incorporated numerous Maple Lake training principles including technical precision emphasis, intensive drilling routines, year-round conditioning programs, mental toughness development, and team-first culture balanced with individual development.

Dozens of wrestlers who trained at Maple Lake became high school and college coaches themselves, creating extensive “coaching trees” where Houk’s influence spread geometrically. A wrestler trained by Houk might coach for 30 years, instructing hundreds of wrestlers who themselves became coaches, creating exponential multiplication of impact. Tracing American wrestling’s most successful programs frequently reveals connections to Maple Lake either through direct participation or training under coaches who learned from Houk-trained mentors.

The camp’s influence extended beyond folkstyle wrestling to freestyle and Greco-Roman styles, as Olympic-trained wrestlers carried techniques and training methods learned at Maple Lake into international competition preparation. American success in international wrestling during the 1970s through 1990s owed significant debt to training systems pioneered and refined at facilities like Maple Lake that systematized preparation rather than relying solely on athletic talent.

Bloomsburg Wrestling’s Continuing Excellence

The wrestling program at Bloomsburg University (formerly Bloomsburg State College) maintained excellence beyond Houk’s coaching tenure, with subsequent coaches building on foundations he established. The university’s wrestling legacy demonstrates how one coach’s vision and program-building can create lasting institutional culture that persists across coaching changes and competitive era shifts.

Bloomsburg wrestlers continued achieving national success for decades after Houk’s departure, with the program producing numerous NCAA All-Americans, national qualifiers, and conference champions while maintaining the technical sophistication and comprehensive preparation that characterized Houk’s teams. This sustained success reflected Houk’s impact on institutional culture, facility development, recruiting networks, alumni engagement, and coaching philosophy continuity.

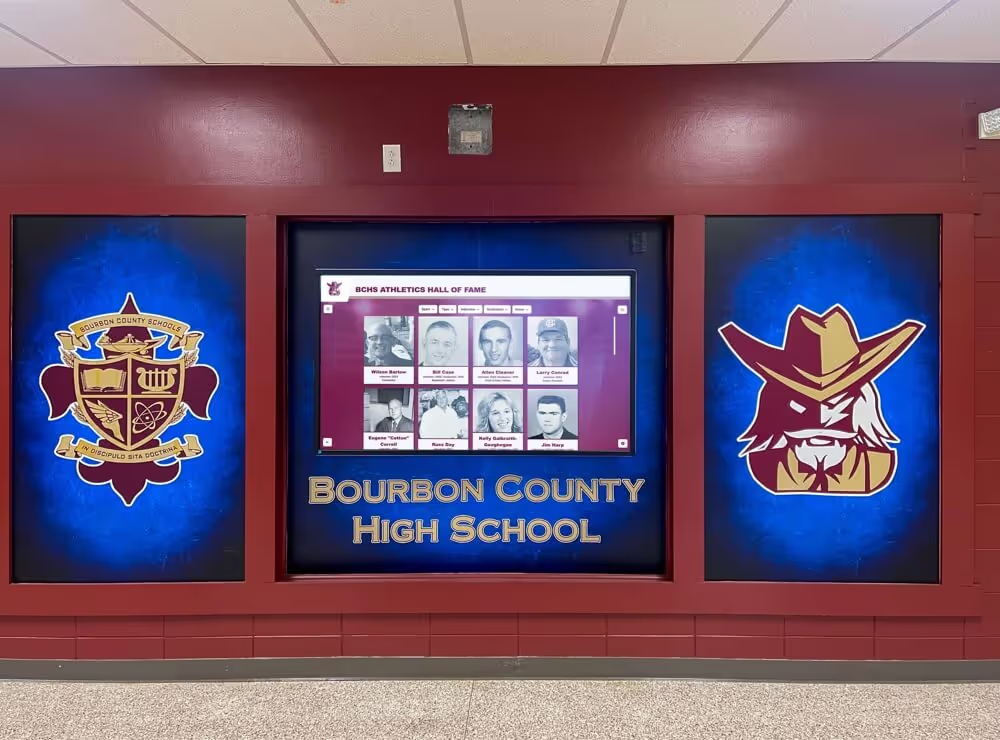

Institutions looking to preserve and celebrate their wrestling heritage should examine how athletic hall of fame programs can honor not just championship teams and individual stars but also foundational coaches whose vision built programs that achieved sustained excellence across generations.

The Camp’s Evolution and Later Years

While the Olympic designation ended in 1973 as USA Wrestling shifted to other training center models, Russ Houk’s camp continued operating and influencing wrestling development through subsequent decades.

Post-Olympic Era Operations (1974-1990s)

After the Olympic training center designation concluded, the camp at Maple Lake continued serving regional wrestlers seeking intensive summer training. While no longer hosting national team preparations, the camp maintained its reputation for quality instruction and effective training methodologies, attracting wrestlers from throughout the Mid-Atlantic region and beyond.

The camp’s focus shifted somewhat from elite Olympic preparation toward comprehensive wrestler development across skill levels, expanding programs for youth wrestlers beginning their competitive careers, intensive training for high school wrestlers preparing for collegiate competition, technique refinement for college wrestlers seeking competitive edges, and coaching education for wrestlers transitioning to instructional roles.

This broader mission reflected changing landscapes in American wrestling as more camps emerged throughout the country, creating competition for elite wrestlers’ attendance while expanding opportunities for wrestlers at all levels to access quality instruction. Maple Lake adapted to this evolving environment while maintaining the training quality and technical sophistication that had distinguished it since 1962.

Succession and Continued Operations

As Houk aged and eventually retired from active camp management, the facility’s operations transitioned to other directors while maintaining connections to its founder’s legacy. The camp continued operating under various names and management structures through the 1980s and 1990s, serving new generations of wrestlers while preserving training philosophies Houk had established.

The transition challenges many athletic programs face when legendary founders retire demonstrate the importance of institutional memory preservation and legacy documentation. Wrestling programs and schools should consider how digital recognition displays can maintain connections to foundational figures and historical achievements even as programs evolve and personnel change, ensuring that founding visions remain visible and influential for current participants.

Recognition and Honors for Russ Houk

Houk’s extraordinary contributions to wrestling earned numerous recognitions throughout and following his career. He was inducted into the Bloomsburg University Athletics Hall of Fame in 1982, among the early inductees in a program recognizing the institution’s most distinguished athletic figures. This honor acknowledged both his coaching excellence and his broader impact on university athletics during a transformative period.

The National Wrestling Hall of Fame recognized Houk’s contributions to American wrestling, documenting his Olympic committee service, camp innovations, and coaching success as part of the sport’s historical record. While many wrestling fans recognize names like Dan Gable or John Smith, fewer know of coaches like Houk whose behind-the-scenes work built systems enabling such athletes to flourish—making historical recognition of foundational figures particularly important for preserving complete understanding of sports development.

Bloomsburg University maintains recognition of Houk’s legacy through various memorials and historical documentation, ensuring current students and athletes understand the program’s foundations and the individuals whose vision built wrestling excellence. Modern institutions should ensure comprehensive recognition programs that celebrate not just championship results but also the coaches, administrators, and visionaries whose work created environments where excellence became possible.

Impact on Wrestling Program Development Nationwide

Russ Houk’s influence extended far beyond the wrestlers he personally coached, shaping how wrestling programs developed throughout American high schools and colleges.

Establishing Comprehensive Training Cultures

Houk demonstrated that wrestling success required comprehensive programming addressing multiple development dimensions simultaneously rather than focusing narrowly on competitive performance. His programs at both Bloomsburg and Maple Lake integrated technical skill development through systematic instruction and progressive drilling, physical conditioning tailored to wrestling’s specific demands, mental preparation addressing competition psychology, nutritional education supporting proper weight management, academic support ensuring wrestlers maintained eligibility and graduated, and character development emphasizing sportsmanship and leadership.

This holistic approach became a model for comprehensive wrestling program development, influencing how successful programs structured their operations. Wrestling programs at schools like Iowa, Iowa State, Oklahoma State, and Penn State—which dominated national competition for decades—incorporated similar comprehensive approaches addressing all aspects of wrestler development rather than treating wrestling as merely physical competition.

Schools developing or strengthening wrestling programs should examine how athletic recognition programs can support program culture by celebrating diverse achievements including technical excellence, academic success, leadership development, and community contribution alongside competitive victories, creating comprehensive definitions of wrestling success.

Year-Round Training and Off-Season Development

Houk pioneered year-round wrestling development at a time when most programs operated primarily during competitive seasons, with minimal organized activity during off-seasons. His summer camp model demonstrated that skill development continued most effectively through consistent year-round training rather than compressed seasonal preparation.

This philosophy influenced how competitive programs structured annual training cycles, establishing off-season strength and conditioning programs, technique clinics during spring and summer, competition opportunities through freestyle and Greco-Roman tournaments, training camps providing intensive skill development, and individualized development plans addressing specific weaknesses. The year-round training model Houk helped establish became standard for competitive wrestling programs, contributing to dramatic skill level increases across American wrestling during subsequent decades.

Programs implementing year-round training should consider how digital recognition systems can celebrate off-season achievements including tournament victories, camp attendance, leadership development, and skill progression, ensuring wrestlers receive recognition for comprehensive development rather than only in-season results.

Coaching Education and Professional Development

Houk’s camp model provided coaching education alongside wrestler training, as young coaches observed training methodologies, instructional techniques, and program management approaches they could implement in their own programs. This mentoring dimension of camp operations created professional development opportunities for coaches that were rare in 1960s and 1970s athletics.

Many wrestlers who attended Maple Lake primarily as participants returned years later as coaches or assistant instructors, learning teaching methodologies through practical apprenticeship under Houk’s supervision. This coaching education model influenced how wrestling coaching expertise transmitted across generations, creating informal but effective professional development systems complementing the limited formal coaching education available during that era.

Modern coaching education has become more structured and systematic, but the principle Houk demonstrated—that camps serve dual purposes providing both wrestler training and coach education—remains valuable. Wrestling programs and state associations should ensure recognition programs honor coaching excellence alongside competitive achievement, celebrating mentors whose teaching developed future generations even when they didn’t personally achieve competitive fame.

Modern Applications: Preserving Wrestling Heritage

Schools, universities, and wrestling organizations seeking to honor their wrestling heritage and maintain connections to foundational figures like Russ Houk can implement several approaches ensuring historical memory informs current programs.

Comprehensive Recognition Programs

Effective wrestling recognition programs should celebrate diverse achievement categories that capture the sport’s multifaceted nature, including individual competitive excellence through tournament championships and records, team success including dual meet championships and tournament titles, coaching achievement recognizing both win-loss records and wrestler development, pioneering contributions from founders and innovators who built programs, significant milestones like program anniversaries or facility dedications, and community impact from wrestlers and coaches who served beyond competitive contexts.

Traditional recognition approaches like trophy cases and championship banners serve important purposes but face limitations in comprehensiveness, as physical space constraints force difficult choices about which achievements receive recognition. Programs with long histories accumulate more accomplishments than can be displayed physically, resulting in selective recognition that may overlook foundational achievements in favor of recent successes.

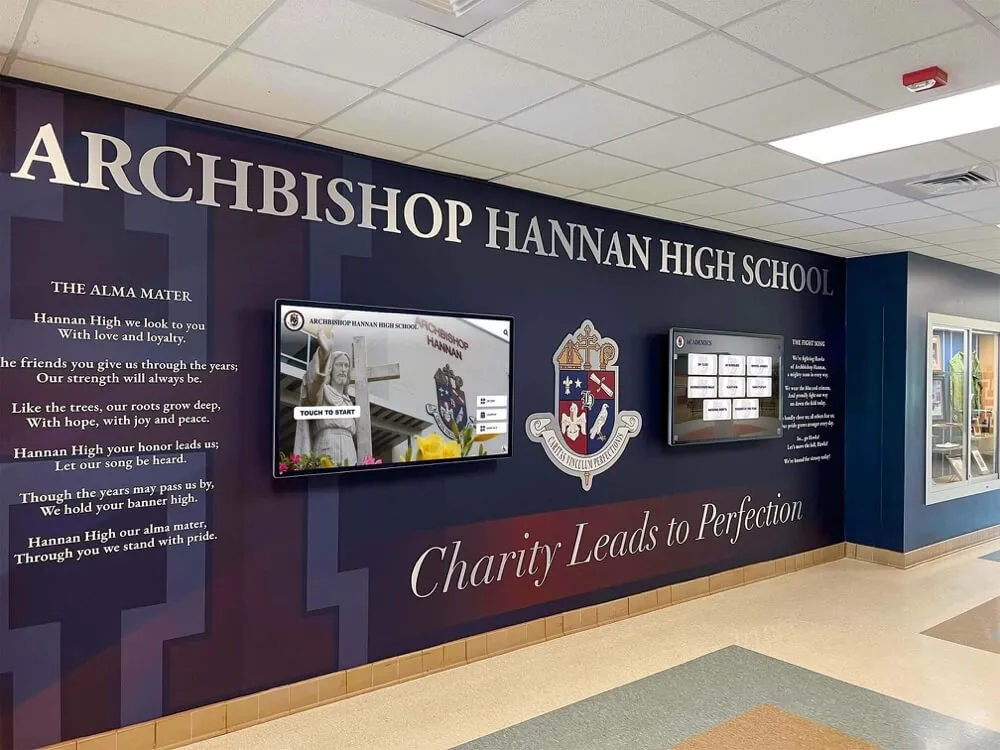

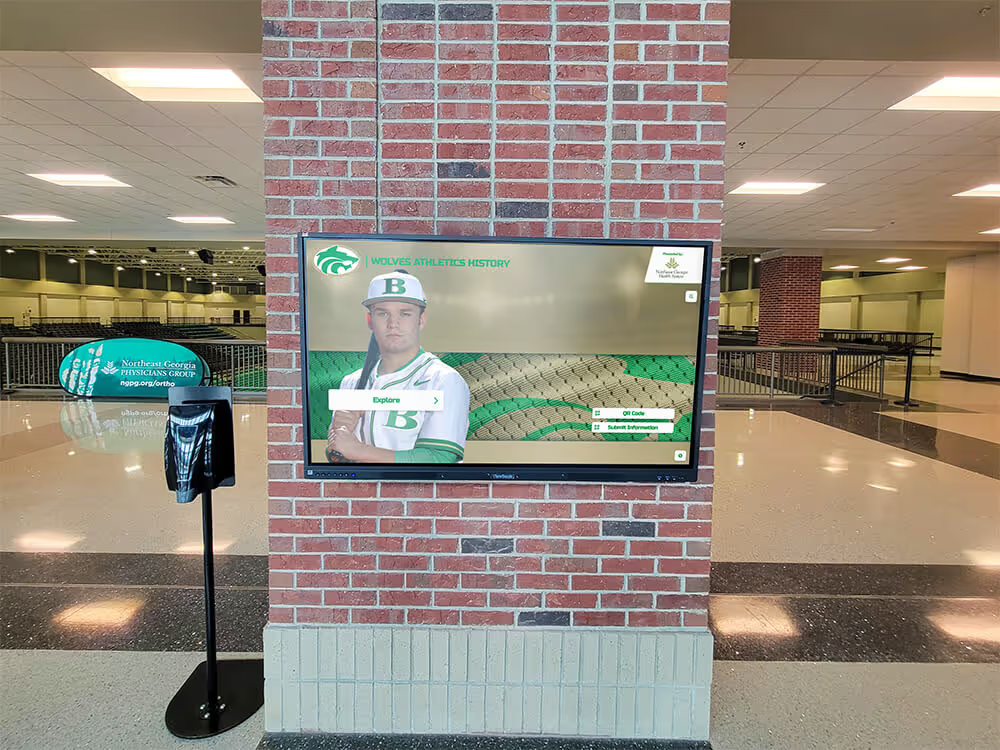

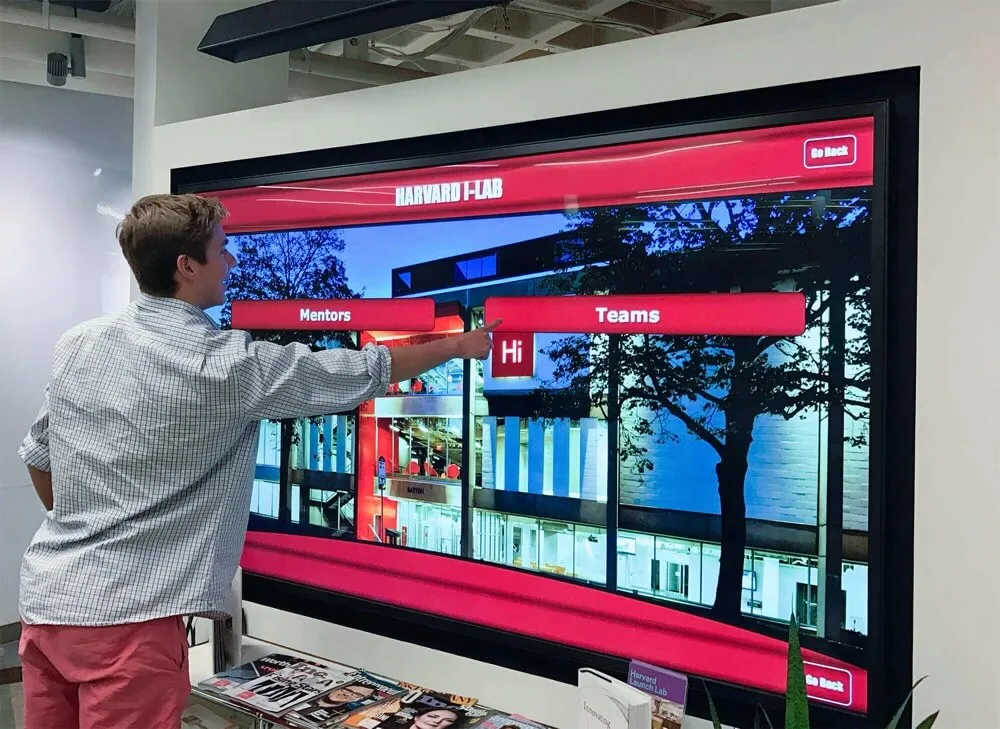

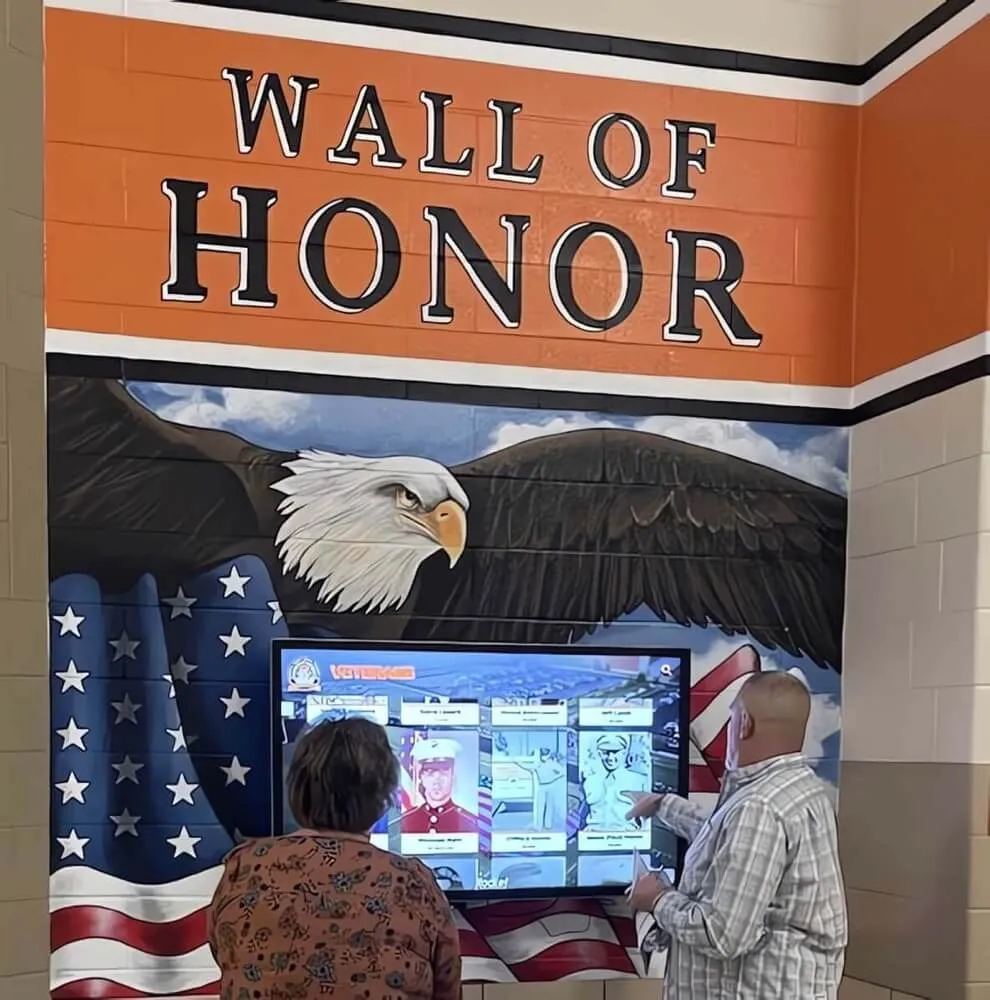

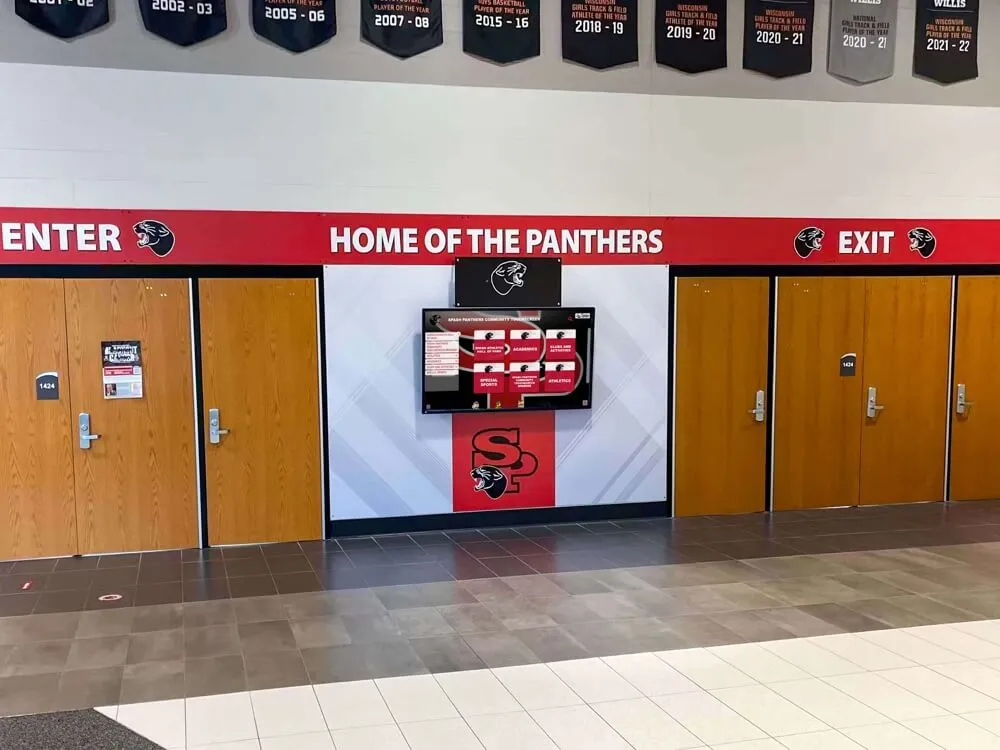

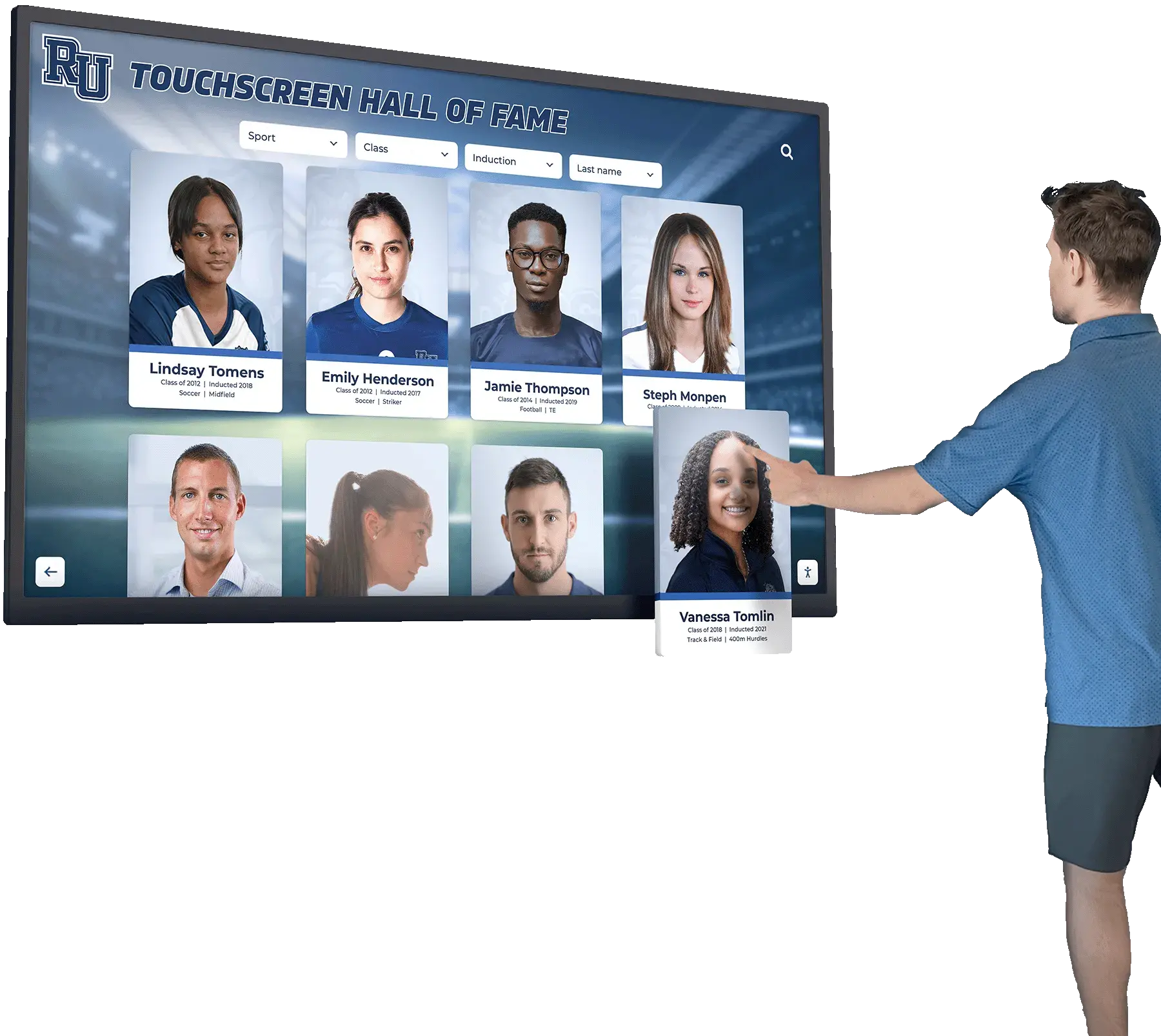

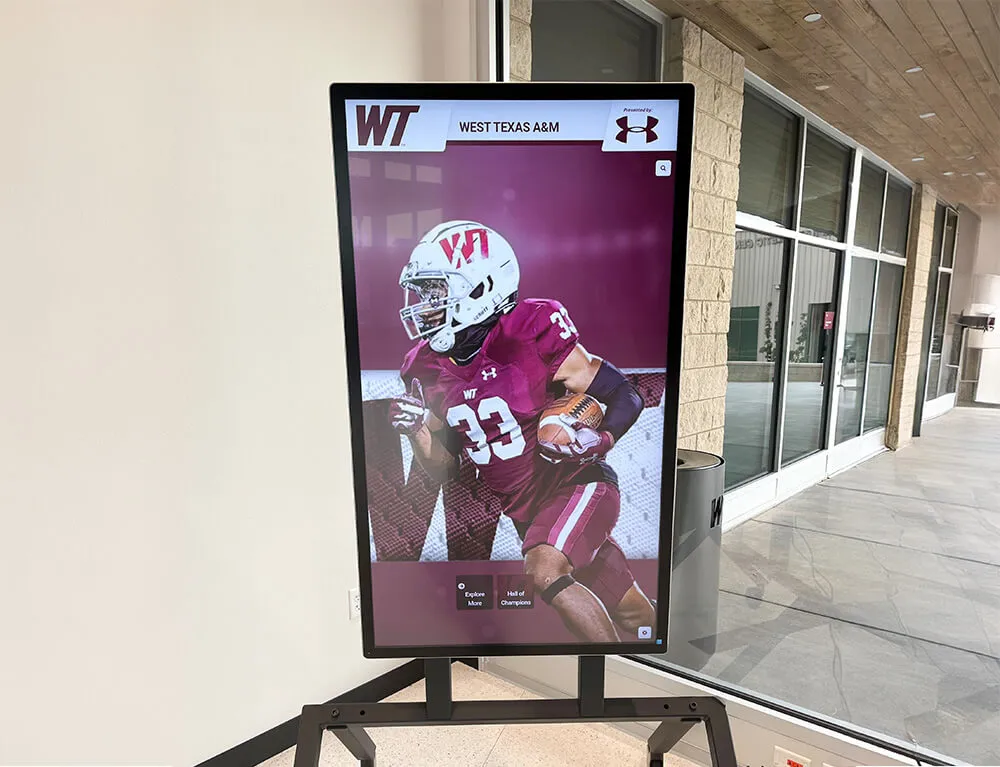

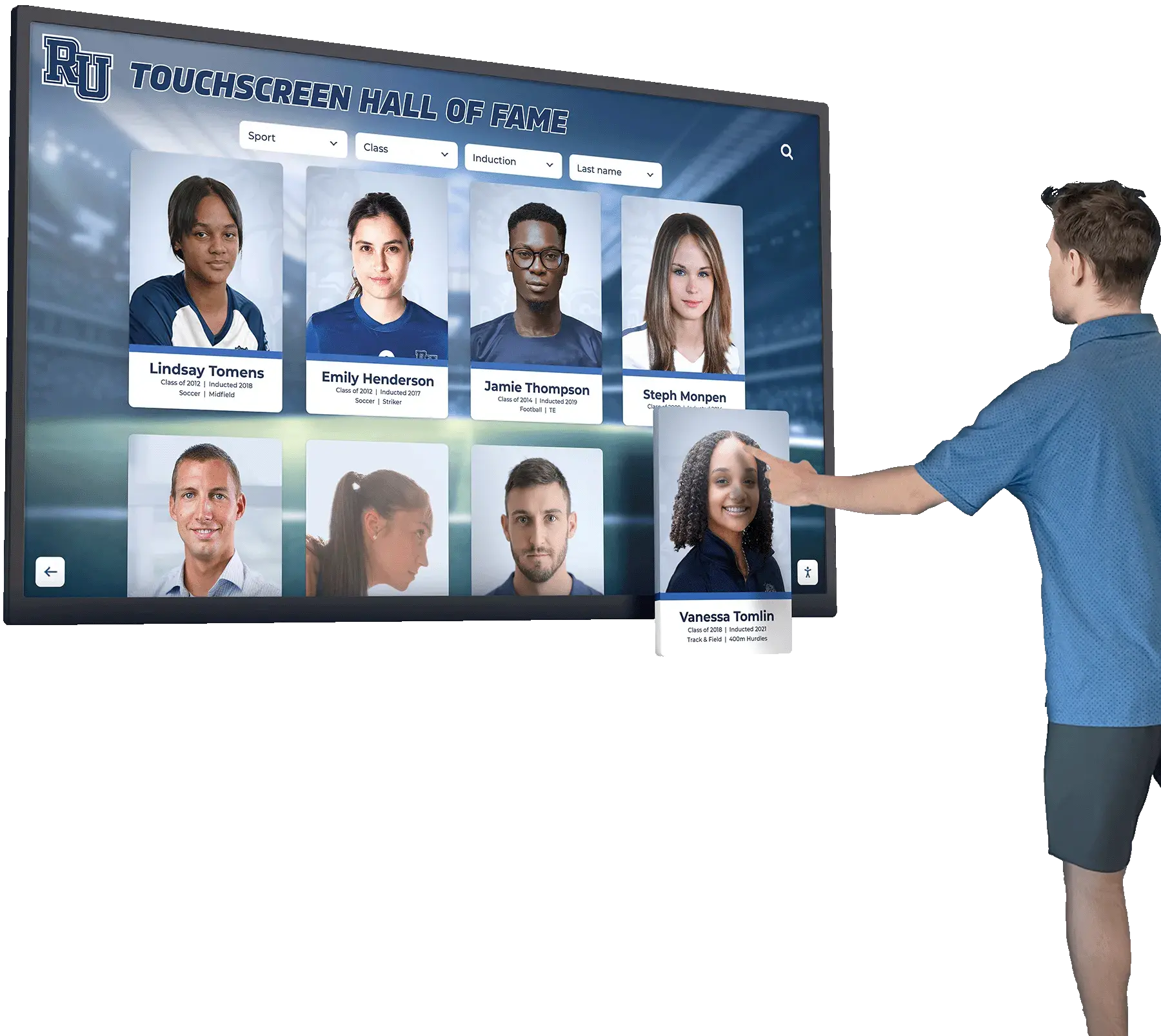

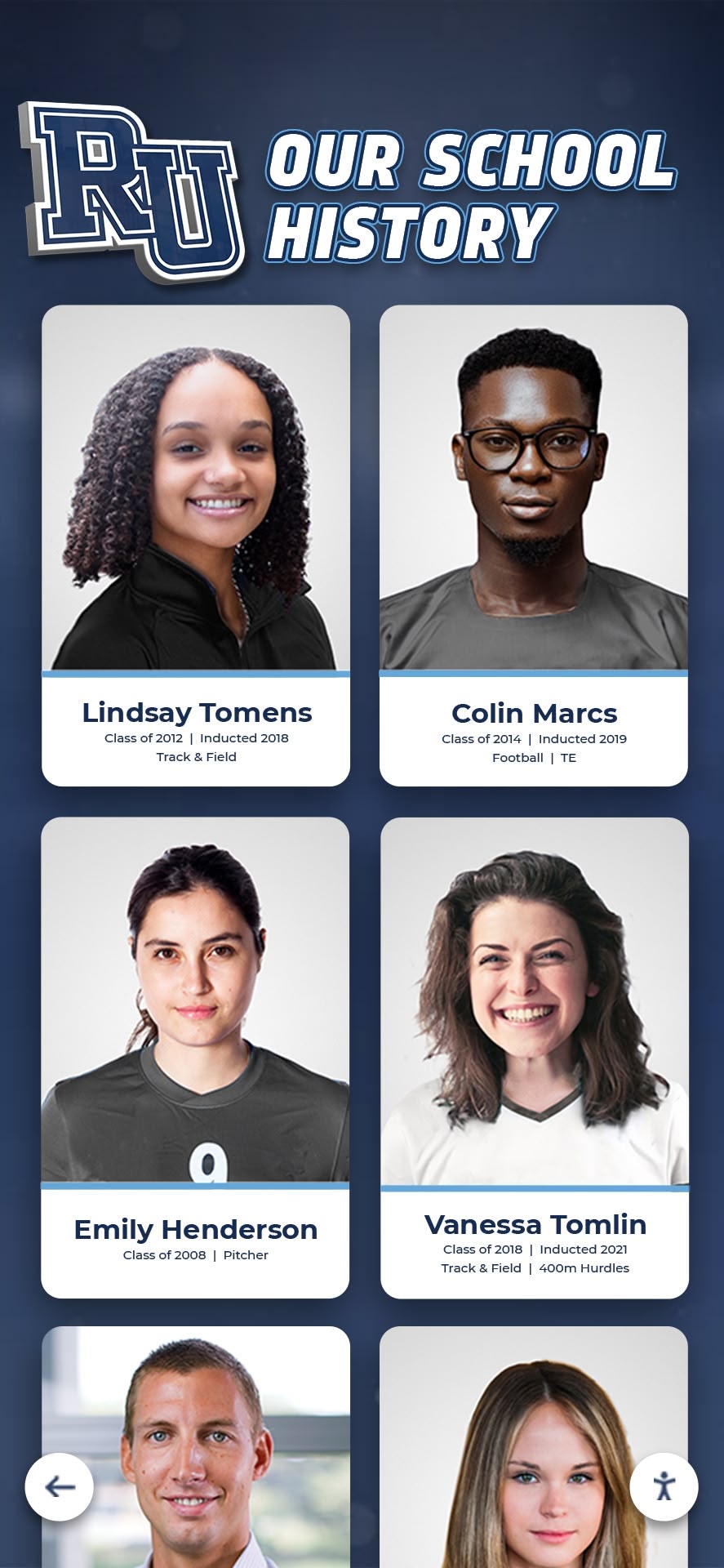

Solutions like Rocket Alumni Solutions’ digital recognition displays address these limitations by providing unlimited capacity to honor all significant achievements without space constraints, multimedia capabilities incorporating historical photos, video footage, and audio recordings bringing history alive, searchable databases allowing community members to explore specific wrestlers, teams, or time periods, easy updates enabling immediate recognition of current achievements while maintaining historical content, and cost-effectiveness compared to expanding physical displays or creating printed historical documents.

Schools implementing wrestling recognition should examine how digital hall of fame displays enable comprehensive celebration of wrestling heritage while providing engaging experiences for current students, alumni, recruits, and community members exploring program history.

Documenting Coaching Legacies

Foundational coaches like Russ Houk deserve recognition that goes beyond win-loss records to capture their broader impact on programs, athletes, and sports development. Comprehensive coaching recognition should document competitive achievements including championships and records, coaching philosophies and training methodologies that distinguished their approaches, athlete development tracking how wrestlers improved and progressed, coaching trees documenting wrestlers who became coaches themselves, innovations and contributions advancing the sport beyond individual programs, and personal narratives capturing coaches’ personalities, values, and relationships with wrestlers.

This comprehensive documentation becomes increasingly important as time passes and direct memories fade. Programs should systematically collect coaching history through oral history interviews with former wrestlers and assistant coaches, documentation of training methods, philosophies, and practice structures, historical photographs and video footage of coaching moments, statistical tracking of coaching records and wrestler development, and recognition of coaching influence beyond immediate program through mentoring and professional development.

Wrestling programs should explore how teacher and staff recognition programs can serve as models for coaching recognition, celebrating educational and developmental impact alongside competitive results.

Connecting Historical Achievement to Current Programs

Effective wrestling heritage recognition doesn’t simply archive history but actively connects historical achievements to current program culture, creating continuity that strengthens institutional identity and competitive motivation. This connection occurs through recognition visibility in training facilities where wrestlers see daily reminders of program heritage, storytelling emphasizing how current programs build on historical foundations, mentoring opportunities connecting current wrestlers with program alumni, tradition continuation maintaining rituals and practices from successful historical periods, and competitive inspiration using historical achievement to motivate current excellence.

Schools should ensure wrestling recognition integrates with current program operations rather than existing as separate historical archives disconnected from daily activity. Placing recognition displays in wrestling rooms, athletic training facilities, or main building entrances creates regular interaction with heritage, while purely archived historical materials rarely influence current program culture effectively.

Programs developing comprehensive wrestling recognition should examine how athletic building displays can showcase historical achievements alongside current season information, creating seamless integration of past excellence with present competition that strengthens program identity across generations.

Lessons From Russ Houk’s Camp for Modern Programs

Contemporary wrestling programs, summer camps, and athletic organizations can draw valuable lessons from the Maple Lake experience that remain relevant despite dramatic changes in sports development since the 1960s and 1970s.

Vision and Innovation in Program Development

Houk’s success stemmed partly from willingness to innovate rather than simply replicating existing approaches. In 1962, few comprehensive wrestling camps existed, making his venture entrepreneurial and risky. The innovation required recognizing that existing training models were insufficient, envisioning improved alternatives despite limited precedents, taking calculated risks implementing unproven approaches, adapting based on results rather than rigidly following initial plans, and persisting through challenges inevitable when pioneering new models.

Modern programs face different challenges but can apply similar innovative thinking when developing recognition systems, training methodologies, recruiting approaches, or community engagement strategies. The lesson from Maple Lake is that program excellence requires creative thinking that goes beyond replicating competitor approaches, even when innovation involves risk and uncertainty.

Programs exploring innovative approaches to recognition should examine how digital recognition technology enables program elements impossible with traditional physical displays, creating opportunities for innovation in how schools celebrate achievement and engage communities.

Quality Over Scale in Program Growth

While Maple Lake eventually became the Olympic training center hosting the nation’s elite wrestlers, it began modestly as a regional camp serving Pennsylvania wrestlers. Houk focused initially on program quality—effective instruction, comprehensive training, safe environment, personal attention—rather than rapid expansion. This quality foundation built the reputation that eventually attracted elite athletes, demonstrating that sustainable growth stems from excellence rather than marketing.

Modern programs often face pressure for rapid expansion and immediate results, but Maple Lake’s trajectory suggests that patient program-building focusing on quality creates more sustainable success than rushed growth prioritizing quantity over excellence. Wrestling programs should ensure training quality, coaching expertise, and wrestler development remain central priorities even when pressure exists to expand program size or generate quick results.

This lesson applies equally to recognition programs, where comprehensive celebration of genuine achievement creates more meaningful impact than superficial recognition of questionable accomplishments simply to generate content. Quality recognition programs should celebrate truly significant achievements thoroughly rather than superficially acknowledging everything in pursuit of recognition quantity.

Long-Term Impact Over Immediate Results

Houk’s greatest legacy came not through his own coaching record—though 142-34-4 was exceptional—but through the wrestlers and coaches he influenced who spread his methodologies throughout American wrestling. This multiplicative long-term impact exceeded what he could have achieved through personal coaching alone, demonstrating that developing others creates greater legacy than personal achievement.

Modern coaches and program leaders should consider long-term impact when making program decisions, asking whether approaches develop wrestlers who will positively influence others, create culture that persists beyond current personnel, build systems that enable sustained excellence, and establish traditions connecting current participants with historical foundations. Programs focusing only on immediate competitive results may achieve short-term success but often fail to create lasting legacies that influence sports development across generations.

Wrestling programs should ensure recognition systems celebrate developmental impact alongside competitive results, honoring coaches whose wrestlers became successful coaches themselves, wrestlers who mentored younger competitors, and program leaders who built sustainable excellence. Schools implementing alumni recognition programs can highlight how former wrestlers contribute to programs as coaches, mentors, donors, or ambassadors, demonstrating that program impact extends far beyond competitive careers.

Celebrating Wrestling Achievement in the Digital Age

Modern technology enables wrestling programs to celebrate achievement more comprehensively and engagingly than was possible during Russ Houk’s era, when recognition relied entirely on physical trophies, plaques, and banners.

Comprehensive Digital Wrestling Recognition

Digital recognition platforms designed for educational athletics provide ideal solutions for comprehensive wrestling celebration, offering tournament results and championship documentation capturing individual and team success, wrestler profiles featuring career statistics, records, and achievements, coaching recognition documenting both competitive records and developmental impact, historical timelines showing program evolution across decades, multimedia integration incorporating photos, video highlights, and audio recordings, and searchable databases enabling exploration by year, weight class, achievement type, or individual name.

These capabilities enable wrestling programs to preserve and celebrate their complete histories rather than selectively recognizing recent achievements due to space limitations. Programs with 50-year wrestling histories can document every conference champion, state qualifier, and significant milestone while maintaining recognition currency by immediately adding current season results.

Schools implementing wrestling recognition should examine how solutions like digital record boards enable comprehensive achievement tracking across all sports including wrestling, creating unified athletic recognition celebrating diverse competitive excellence.

Interactive Engagement and Community Building

Modern digital recognition creates interactive experiences that passively viewed trophies cannot match, including touchscreen exploration allowing visitors to navigate wrestling history at their own pace and interest, video highlights showing championship matches and technique demonstrations, statistical comparisons enabling fans to compare wrestlers across eras, social sharing features allowing wrestlers and families to share recognition through social media, and alumni updates documenting post-competitive careers and ongoing connections to programs.

These interactive elements transform recognition from static display to engaging experience that strengthens community connections, maintains alumni relationships, and inspires current wrestlers by demonstrating the excellence achieved by those who preceded them. Wrestling programs can use digital recognition to build community around shared heritage rather than simply documenting past accomplishments.

Programs exploring comprehensive wrestling recognition should examine how Division I athletics recognition creates engaging experiences celebrating athletic excellence at the highest competitive levels, providing models applicable to wrestling programs at all competitive tiers.

Preserving Wrestling Heritage for Future Generations

Digital recognition platforms provide superior long-term preservation compared to physical displays that deteriorate, get lost during facility renovations, or become damaged over time. Digital systems enable secure backup ensuring achievement records persist indefinitely, easy migration as technology evolves preventing obsolescence, continuous updating maintaining historical accuracy as new information emerges, format flexibility adapting to changing display technologies, and unlimited replication allowing recognition to appear in multiple locations simultaneously.

Wrestling programs implementing digital recognition today ensure that achievements of current wrestlers will be preserved and accessible decades into the future, just as programs now wish they had comprehensive documentation of wrestlers from the 1960s through 1980s when many competed before systematic record-keeping existed.

Schools should prioritize wrestling heritage preservation through systematic documentation efforts including oral history interviews with retired coaches and alumni wrestlers, digitization of historical photographs, newspaper clippings, and documents, video preservation of championship matches and historical footage, statistical compilation creating comprehensive records databases, and recognition system implementation showcasing historical achievements alongside current success.

Programs exploring heritage preservation should examine how school history displays can showcase wrestling alongside broader institutional history, demonstrating how athletic programs contribute to overall school identity and tradition.

Conclusion: Honoring Wrestling Excellence Across Generations

Russ Houk’s wrestling camp legacy demonstrates how visionary leadership, innovative training methodologies, and commitment to comprehensive athlete development can influence sports far beyond immediate coaching achievements. The camp established at Maple Lake in 1962 pioneered training approaches that shaped American wrestling during its most successful international era, producing Olympic champions, establishing coaching methodologies adopted nationwide, and creating a legacy that continues influencing wrestling program development today.

For contemporary wrestling programs, Houk’s example offers valuable lessons about prioritizing program quality over rapid expansion, focusing on long-term impact rather than immediate results, innovating rather than simply replicating competitor approaches, developing comprehensive athlete preparation addressing technical, physical, and mental dimensions, and building cultures that persist across coaching changes and competitive era shifts. These principles remain as relevant today as during Maple Lake’s Olympic era, providing guidance for programs seeking sustained excellence across generations.

Schools, universities, and wrestling organizations honoring their sport’s heritage should implement comprehensive recognition programs that celebrate not just championship results but also the coaches, training innovations, and developmental approaches that built competitive excellence. Digital recognition platforms enable this comprehensive celebration through unlimited capacity accommodating complete program histories, multimedia capabilities bringing historical achievements to life, interactive experiences engaging current wrestlers and community members, and sustainable systems preserving wrestling heritage for future generations.

As wrestling continues evolving with new training methodologies, competitive formats, and technologies, maintaining connections to foundational figures like Russ Houk ensures current programs build on proven excellence rather than discarding valuable traditions. Comprehensive recognition honoring wrestling’s past while celebrating present achievement creates program cultures where historical legacy inspires current excellence—exactly the environment Houk created at Maple Lake where Olympic champions trained alongside aspiring high school wrestlers, all connected through shared commitment to wrestling excellence that transcended individual competitive ambition.

Ready to Honor Your Wrestling Program’s Legacy?

Discover how comprehensive digital recognition displays can celebrate wrestling achievement across all levels—from youth competitors through Olympic champions—while preserving program heritage for future generations. Explore Rocket Alumni Solutions to see how schools and universities nationwide use interactive touchscreen technology to honor wrestling excellence, maintain alumni connections, and inspire current athletes through comprehensive celebration of program history and achievement.

From athletic hall of fame displays to state championship recognition, the right digital recognition solutions make it easier to implement comprehensive programs celebrating wrestling heritage while building community around shared competitive traditions that connect past champions with present wrestlers pursuing their own excellence.