Key Takeaways

Discover the complete history of consolidated schools merging in America, from one-room schoolhouses to modern educational complexes. Learn how consolidation shaped rural education and community identity across generations.

The One-Room Schoolhouse Era: Education Before Consolidation

To understand school consolidation, we must first recognize what existed before—the ubiquitous one-room schoolhouse that defined American rural education for generations.

The Golden Age of Rural Schools

Throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century, one-room schoolhouses dotted the American landscape. In 1918, the United States had approximately 196,000 one-room schools serving rural communities. These small, locally controlled institutions typically enrolled 10 to 30 students spanning all grade levels, taught by a single teacher who managed instruction across multiple subjects and ages simultaneously.

Characteristics of One-Room Schools:

- Local Control: Community members directly managed their schools, hiring teachers, maintaining buildings, and setting curriculum priorities

- Walking Distance: Schools were positioned so all students could walk from home, typically within two to three miles

- Multi-Age Learning: Older students often helped teach younger ones, creating mentorship opportunities

- Community Centers: Schoolhouses served as gathering places for social events, town meetings, and celebrations

- Limited Resources: Most schools operated with minimal funding, basic supplies, and teachers who often lacked formal training

These schools reflected the agricultural economy and settlement patterns of rural America. Families depended on children’s labor during planting and harvest seasons, making nearby schools with flexible attendance more practical than distant institutions with rigid schedules.

Early Challenges and Criticisms

By the early 1900s, educational reformers began identifying significant limitations in the one-room school model:

Educational Quality Concerns:

- Wide variance in teacher qualifications and instructional effectiveness

- Limited curriculum breadth, particularly in advanced subjects and sciences

- Inadequate facilities, often lacking proper heating, lighting, or sanitation

- Insufficient educational materials and equipment for effective instruction

- No standardized assessment or quality control across districts

Economic Inefficiencies:

- High per-pupil costs due to small enrollment numbers

- Duplication of administrative expenses across thousands of tiny districts

- Inability to attract and retain qualified teachers with competitive compensation

- Limited purchasing power for instructional materials and equipment

- Difficulty maintaining aging buildings with small tax bases

These concerns gained prominence as American society industrialized and urbanized. Educational leaders observed that urban children attending graded schools with specialized teachers appeared to receive superior preparation compared to rural students in one-room schoolhouses.

The Birth of School Consolidation Movement (1890s-1930s)

The consolidation movement emerged from progressive era reform efforts aimed at applying business efficiency principles to public institutions, including education.

Ideological Foundations

Early consolidation advocates drew inspiration from several converging influences:

Efficiency Movement: Industrial efficiency experts argued that larger schools could achieve economies of scale, reducing per-pupil costs while improving educational quality. They believed that professional administrators managing larger districts would operate more effectively than thousands of small community boards.

Professional Education Standards: University-trained educators promoted standardized curriculum, age-graded classrooms, and specialized instruction. They viewed consolidation as necessary for implementing these professional standards that one-room schools couldn’t support.

Rural Life Reform: Some reformers believed consolidation would modernize rural communities, connecting them to urban progress and reducing perceived cultural isolation. They saw larger schools as catalysts for broader rural development.

Child-Centered Learning: Educational theorists emphasized that children learned best in age-appropriate peer groups with access to diverse subjects and activities. Consolidated schools could provide specialized instruction, laboratory equipment, libraries, and extracurricular programs impossible in one-room settings.

Early Consolidation Efforts

The first significant consolidation efforts began in the 1890s, concentrated primarily in the Midwest and Northeast:

Massachusetts pioneered early consolidation legislation in 1869, allowing towns to close small rural schools and transport students to centralized facilities. However, widespread implementation didn’t occur until decades later.

Ohio emerged as a consolidation leader in the early 1900s, with state officials actively promoting district mergers and providing financial incentives for communities willing to consolidate.

Indiana, Iowa, and Kansas followed similar paths, with state education departments offering subsidies for transportation and building construction to encourage consolidation.

These early efforts encountered substantial resistance from rural communities who valued local control and viewed consolidation as urban interference in their affairs. Many families opposed sending young children long distances, particularly given poor road conditions and unreliable transportation.

Transportation Enables Consolidation

The consolidation movement couldn’t succeed without solving the transportation challenge. Students couldn’t attend distant consolidated schools if they couldn’t reliably travel there.

Horse-Drawn School Wagons: In the 1890s and early 1900s, some consolidated districts experimented with horse-drawn wagons to transport students. These proved expensive, unreliable in poor weather, and uncomfortable for children during winter months.

Motorized School Buses: The introduction of motorized vehicles transformed consolidation feasibility. The first motorized school bus appeared in 1914, and by the 1920s, purpose-built school buses were being manufactured specifically for student transportation. This technological advancement made consolidation practical across much larger geographic areas.

Road Improvements: Federal highway construction programs in the 1920s and 1930s improved rural road networks, making school transportation more reliable year-round. Better roads reduced travel times and made consolidated schools accessible to more distant students.

By 1930, approximately 190,000 students rode school buses daily—a number that would multiply exponentially in subsequent decades as consolidation accelerated.

The Great Wave of Consolidation (1930s-1960s)

The decades following the Great Depression witnessed unprecedented school consolidation as economic pressures, policy incentives, and demographic changes combined to reshape American education fundamentally.

Depression-Era Pressures

The economic crisis of the 1930s created intense pressure for school consolidation:

Financial Distress: Rural communities struggled to fund schools as property values plummeted and tax revenues collapsed. Maintaining multiple small schools became financially impossible for many districts.

State Intervention: State governments, concerned about educational quality and fiscal sustainability, increased pressure on small districts to consolidate. Many states passed laws making consolidation easier and provided financial incentives for merging districts.

Federal Support: New Deal programs funded school construction and transportation infrastructure, making consolidation more financially attractive. The Public Works Administration and other federal agencies provided grants and loans for building consolidated schools.

Between 1930 and 1940, the number of one-room schools declined from approximately 149,000 to 114,000—a reduction of about 23% in just one decade, accelerating the consolidation trend.

Post-War Consolidation Boom

The period following World War II witnessed the most dramatic consolidation in American history:

Baby Boom Pressures: Rapidly growing student populations strained existing facilities. Rather than maintaining or expanding numerous small schools, many communities chose to build larger consolidated facilities.

State Mandates: States increasingly mandated minimum school sizes and imposed regulations that small districts couldn’t meet. Between 1945 and 1965, at least 45 states passed legislation explicitly encouraging or requiring consolidation.

Improved Transportation: Post-war highway construction and school bus fleet expansion made transporting students across greater distances practical and affordable. Longer bus routes enabled consolidation across entire counties or multiple townships.

Curriculum Expectations: Growing emphasis on comprehensive education—including advanced sciences, foreign languages, vocational training, and expanded athletics—required resources and specialized teachers that only larger schools could support.

Economic Efficiency Arguments: States demonstrated that consolidated schools delivered education at significantly lower per-pupil costs than maintaining multiple small schools. These efficiency arguments proved compelling to taxpayers and policymakers.

The results were staggering. Between 1940 and 1970:

- The number of school districts decreased from approximately 117,000 to about 18,000

- One-room schools nearly disappeared, declining from 114,000 in 1940 to fewer than 1,000 by 1970

- Average school district size increased from roughly 200 students to over 2,000 students

- Transportation fleets expanded to accommodate millions of rural students traveling to consolidated schools

Regional Variations

While consolidation occurred nationwide, significant regional differences emerged:

Midwest and Great Plains: These regions experienced the most dramatic consolidation. States like Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas, which had thousands of one-room schools serving sparse rural populations, saw districts shrink by 95% or more.

South: Consolidation in Southern states occurred alongside desegregation efforts in the 1950s and 1960s, creating complex dynamics. Some consolidations aimed to improve Black students’ educational access, while others attempted to circumvent desegregation requirements.

Northeast: More densely populated Northeastern states had already begun consolidation earlier, so changes were less dramatic but still significant, particularly in rural areas.

West: Western states with large geographic areas and scattered populations faced unique consolidation challenges, sometimes creating districts covering hundreds of square miles with extensive transportation requirements.

Educational and Philosophical Rationales for Consolidation

Beyond economic arguments, educational leaders promoted consolidation based on pedagogical and developmental principles that shaped mid-20th century educational philosophy.

Comprehensive High Schools

Educational reformers envisioned comprehensive high schools offering diverse academic tracks, extensive extracurricular activities, and specialized facilities that small schools couldn’t provide:

Curriculum Breadth: Consolidated schools could employ specialized teachers for advanced mathematics, sciences, foreign languages, music, and art—subjects often unavailable in small schools.

Vocational Programs: Larger schools supported vocational training programs in agriculture, home economics, shop classes, and business skills, preparing students for diverse career paths.

Advanced Courses: Consolidated schools could offer college preparatory curricula with advanced placement courses, chemistry and physics laboratories, and comprehensive libraries.

Extracurricular Opportunities: Larger student bodies enabled competitive sports teams, debate clubs, drama programs, music ensembles, and other activities believed essential for well-rounded development.

Educational leaders argued that comprehensive consolidated schools would equalize educational opportunities between rural and urban students, preparing all young people for success in an increasingly complex modern economy.

Social and Civic Development

Consolidation advocates believed larger schools provided superior social environments for adolescent development:

Peer Interaction: Age-graded classrooms with adequate student numbers allowed children to interact with same-age peers, believed important for social development.

Competitive Experience: Larger schools prepared students for competitive environments they would encounter in higher education and careers.

Democratic Training: Bigger schools enabled student government, clubs, and organizations that reformers viewed as training grounds for democratic citizenship.

Social Efficiency: Some consolidation advocates promoted social efficiency theories, believing schools should sort students by ability and prepare them for appropriate societal roles—a controversial philosophy that larger schools could implement more systematically.

Teacher Professionalization

Consolidation enabled significant improvements in teacher quality and working conditions:

Higher Salaries: Consolidated districts could offer competitive salaries, attracting better-qualified teachers with stronger educational backgrounds.

Specialization: Larger schools employed subject specialists rather than requiring teachers to instruct all grades and subjects simultaneously.

Professional Support: Consolidated schools provided teachers with professional colleagues, administrative support, and resources unavailable in isolated one-room schools.

Career Advancement: Larger districts created career ladders with opportunities for advancement into department chairs, curriculum specialists, and administrative positions.

These improvements in teaching quality formed a central argument for consolidation that research appeared to support in many cases.

Community Resistance and Loss

While consolidation advocates emphasized educational and economic benefits, many rural communities experienced the closure of their schools as profound loss, triggering resistance that continues echoing today.

Emotional and Identity Attachments

For many rural communities, the local school represented the heart of community identity:

Community Gathering Place: Schools hosted social events, elections, meetings, and celebrations. Their closure eliminated important community spaces.

Local Pride: Community members took pride in “their” school, supporting it through volunteer labor, fundraising, and active participation in governance.

Generational Connections: Families often attended the same schools across multiple generations, creating powerful emotional bonds and shared heritage.

Symbol of Community Viability: An operating school signaled community vitality. School closure often preceded or symbolized broader community decline.

When consolidation threatened these cherished institutions, communities frequently organized opposition campaigns, packed school board meetings, and petitioned state officials to preserve their schools.

Loss of Local Control

The shift from local school boards to distant consolidated district administration fundamentally altered democratic participation:

Distance from Decision-Making: Parents who previously served on local boards influencing daily school operations now had minimal input in large district bureaucracies.

Standardization vs. Local Needs: Consolidated districts implemented standardized policies that sometimes conflicted with local values, traditions, or practical needs.

Reduced Responsiveness: Large district administrations proved less responsive to individual community concerns than local boards accountable to neighbors.

Professional vs. Community Control: Educational professionals increasingly made decisions previously handled by community members, shifting power from parents to credentialed administrators.

These governance changes represented a fundamental shift in American democratic traditions of local control over education.

Economic and Social Consequences

School closures triggered economic and social consequences that extended beyond education:

Economic Impact: Schools often provided community employment. Their closure eliminated teaching positions, custodial jobs, and business from families traveling to school events.

Depopulation: School closure sometimes accelerated rural depopulation as families with children moved to towns with schools, further weakening remaining communities.

Transportation Burdens: Long bus rides consumed significant student time and created logistical challenges for families managing children’s schedules and activities.

Extracurricular Barriers: Distance made student participation in after-school activities more difficult, particularly when parents lacked transportation to retrieve children after practices or events.

Cultural Identity Loss: Consolidated schools sometimes subsumed distinct community identities, traditions, and cultures into homogenized larger institutions.

These consequences meant that while consolidation might improve educational efficiency or quality by some measures, it came with real costs to community cohesion and rural life quality.

The Research Debate: Did Consolidation Improve Education?

The actual educational impacts of consolidation remain debated, with research providing mixed evidence on whether larger schools truly deliver superior outcomes.

Arguments Supporting Educational Benefits

Research supporting consolidation highlighted several advantages:

Curriculum Breadth: Consolidated schools demonstrably offered more courses, particularly in advanced subjects, sciences, and specialized areas. Students gained access to educational opportunities unavailable in small schools.

Teacher Quality: Larger schools employed more credentialed teachers with stronger subject-area training. Higher salaries attracted better-qualified educators.

Facilities and Resources: Consolidated schools featured superior laboratories, libraries, technology, and specialized spaces for athletics, arts, and vocational training.

College Preparation: Studies suggested students from larger schools attended college at higher rates and performed better in higher education, though socioeconomic factors confounded these findings.

Evidence Questioning Consolidation Benefits

However, substantial research questioned whether consolidation truly improved educational outcomes:

Achievement Studies: Many studies found no significant differences in standardized test performance between students from small versus consolidated schools after controlling for socioeconomic factors.

Dropout Rates: Some research indicated small schools had lower dropout rates and stronger student engagement compared to larger consolidated institutions.

Student Belonging: Students in smaller schools reported stronger connections to teachers, greater participation in activities, and more positive school experiences.

Cost-Effectiveness Questions: When factoring in transportation costs, building debt, and administration overhead, per-pupil cost advantages of consolidation proved smaller than claimed.

Optimal Size Debates: Research suggested educational and social benefits plateaued or declined as schools exceeded certain sizes—perhaps 300-600 students for elementary and 600-900 for high schools—raising questions about consolidations creating excessively large institutions.

The research complexity demonstrates that consolidation’s impacts varied significantly based on how it was implemented, what size schools resulted, and how consolidation affected specific communities.

Modern Consolidation Trends and Contemporary Debates

School consolidation didn’t end in the 1970s. While the most dramatic changes occurred mid-century, consolidation pressures continue shaping American education today.

Ongoing Consolidation Pressures

Several factors continue driving consolidation discussions:

Declining Rural Populations: Continued rural depopulation in many regions creates unsustainable small schools with rising per-pupil costs.

State Funding Formulas: Many state funding systems incentivize consolidation by providing additional resources to larger districts or penalizing very small schools.

Educational Mandates: Federal and state requirements for comprehensive curriculum, technology infrastructure, and specialized services strain small district resources.

Teacher Shortages: Small rural districts struggle recruiting specialized teachers in STEM fields, special education, and other high-demand areas.

Athletic Conference Requirements: Athletic leagues increasingly require minimum enrollment levels, forcing very small schools to consolidate or discontinue competitive programs.

These pressures continue prompting consolidation discussions in rural areas, particularly in the Great Plains and Midwest where declining populations make small schools increasingly difficult to sustain.

The Small Schools Movement

Interestingly, even as some rural districts consider consolidation, urban education has embraced “small schools” reform initiatives based on research showing advantages of smaller learning environments:

Personalized Learning: Small schools enable closer student-teacher relationships and more individualized instruction.

Student Engagement: Smaller environments reduce anonymity and increase student participation in activities and school governance.

Safety and Culture: Small schools often report stronger school culture, fewer discipline problems, and enhanced safety.

Urban Applications: Many large urban districts have subdivided comprehensive high schools into smaller learning communities or created new small schools.

This movement creates an ironic situation where urban reformers embrace smallness while rural communities face pressure to consolidate—highlighting how context shapes educational approach appropriateness.

Preserving Heritage in Consolidated Schools

Consolidated schools face the ongoing challenge of honoring the distinct traditions and histories of merged communities while building unified institutional identities.

Heritage Preservation Strategies

Successful consolidated schools implement various approaches to preserve and celebrate merged school legacies:

Historical Documentation: Comprehensive archiving of yearbooks, photographs, athletic records, academic achievements, and institutional histories from predecessor schools ensures this heritage isn’t lost.

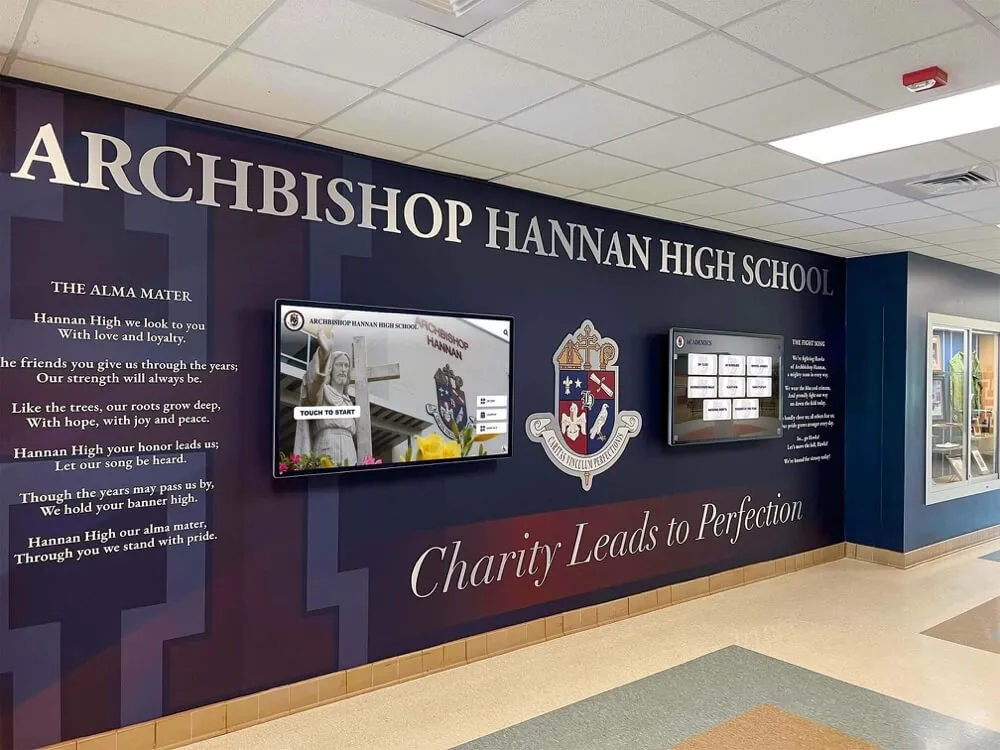

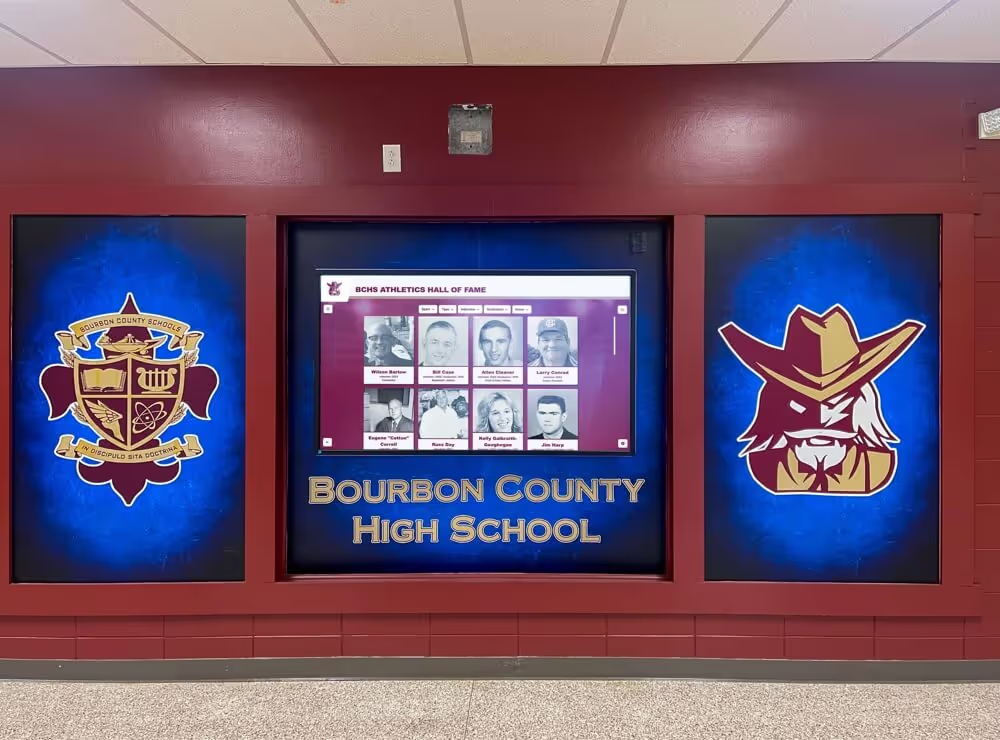

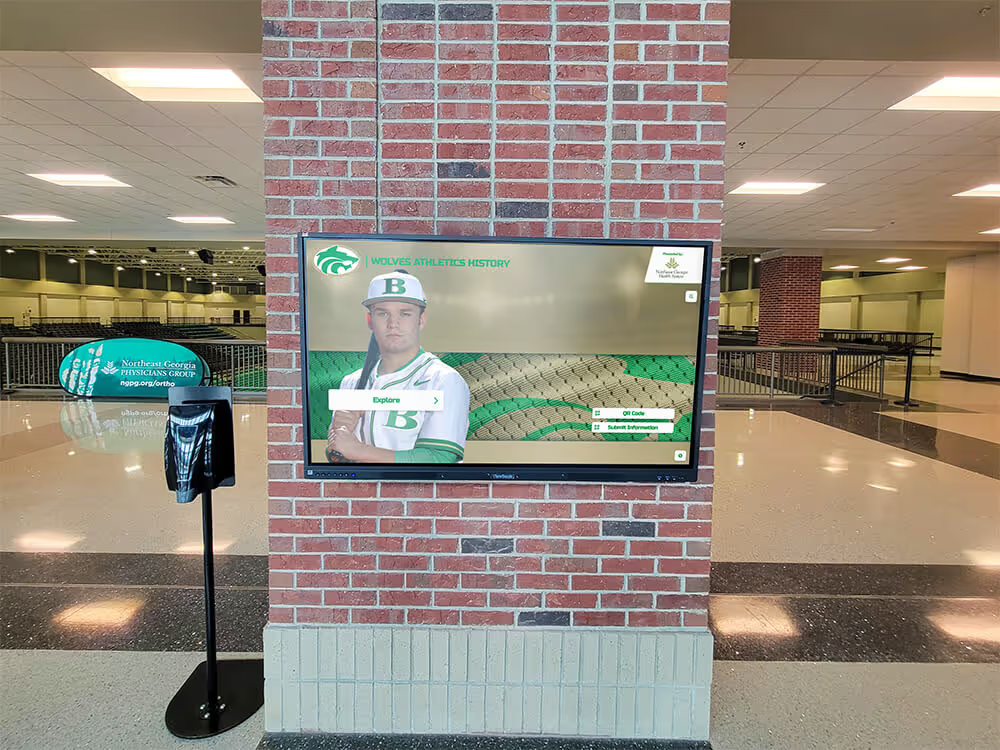

Physical Spaces: Many consolidated schools create dedicated areas displaying artifacts, photographs, and memorabilia from merged institutions, providing tangible connections to historical schools.

Tradition Integration: Thoughtfully incorporating colors, mascots, songs, or traditions from predecessor schools into new institutional identity demonstrates respect for merged communities.

Alumni Engagement: Active alumni associations for predecessor schools maintain connections across generations while supporting the consolidated institution.

Anniversary Celebrations: Marking milestone anniversaries of both the consolidated school and predecessor institutions honors all aspects of institutional heritage.

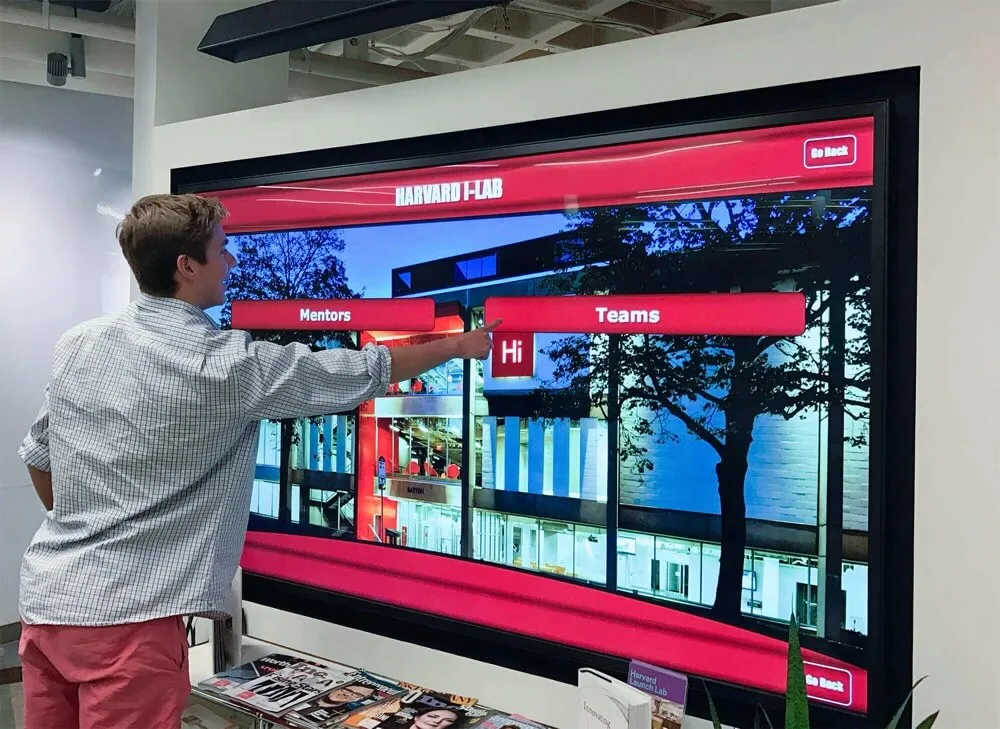

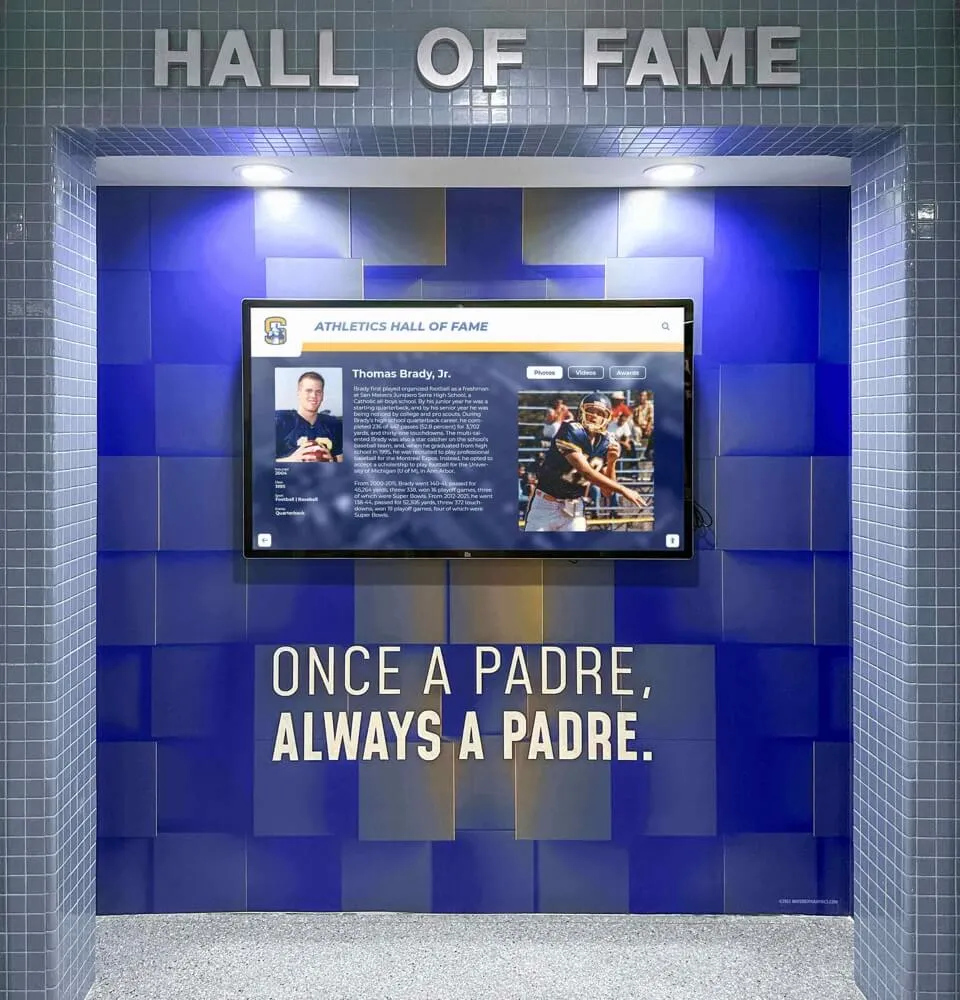

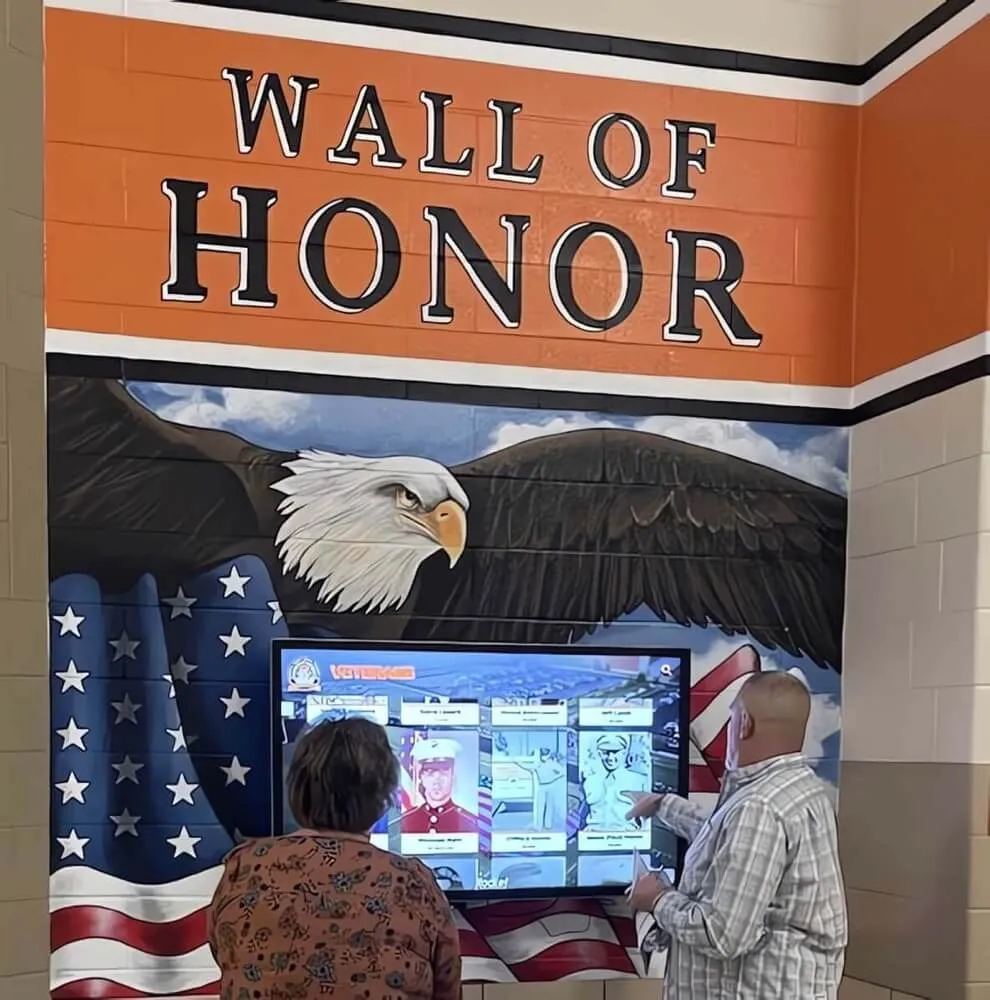

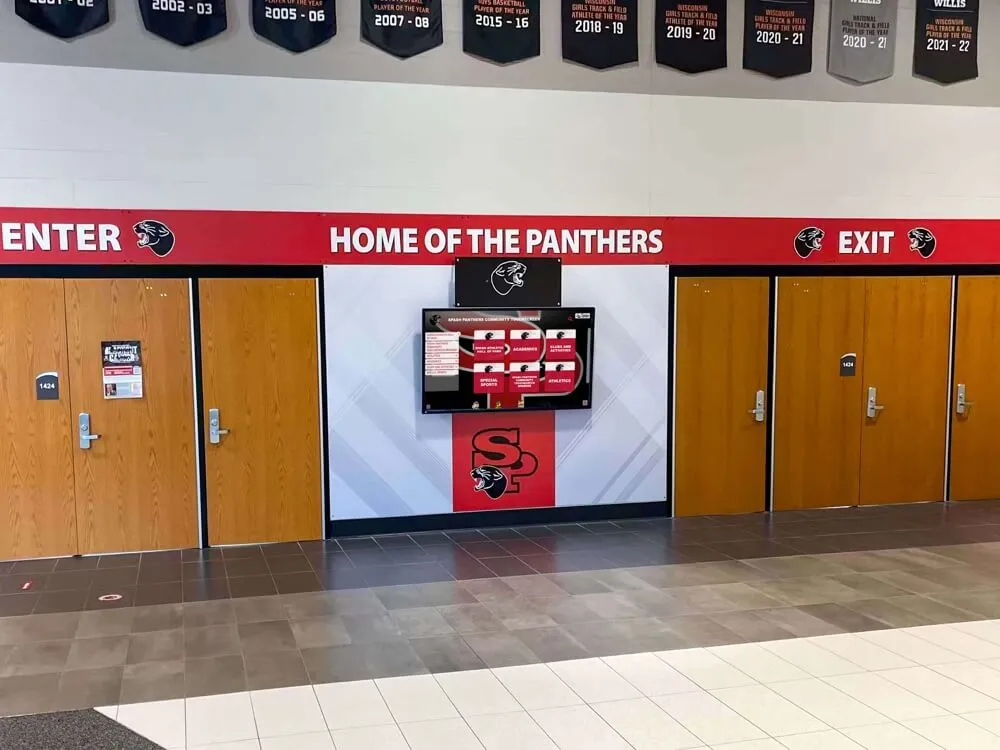

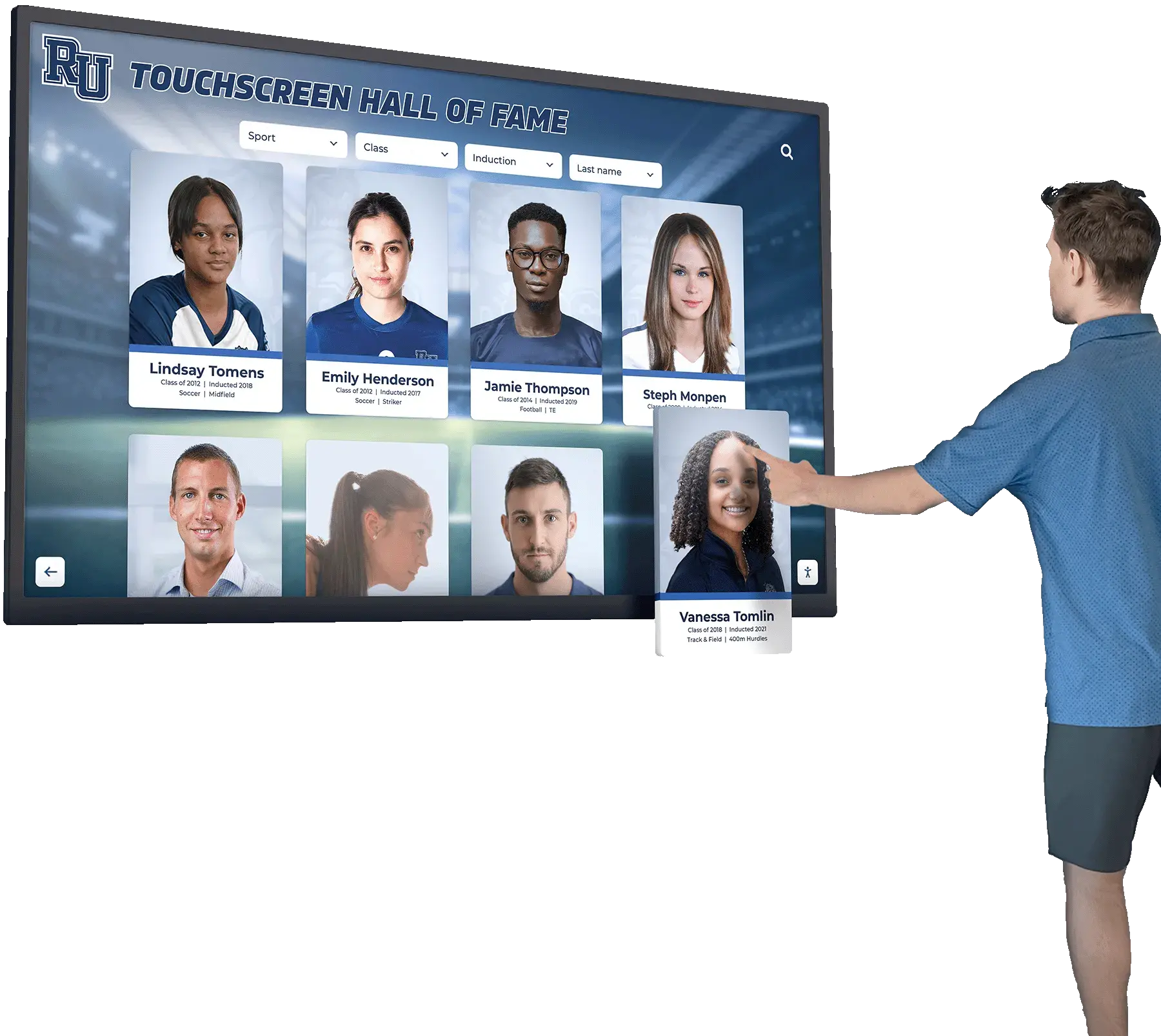

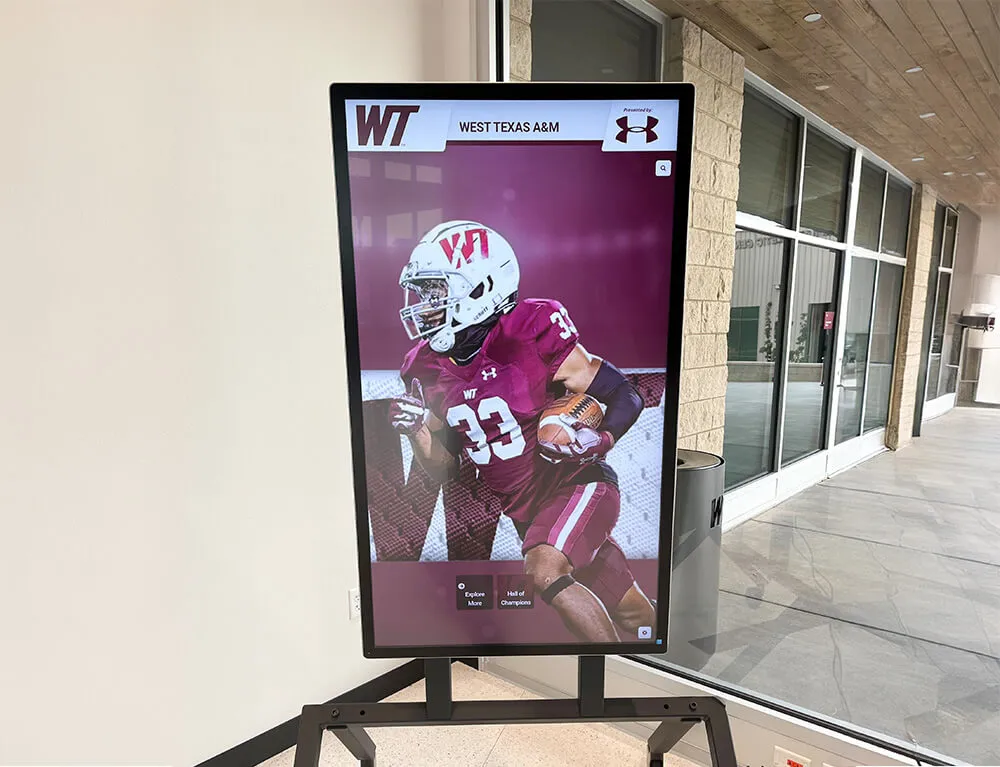

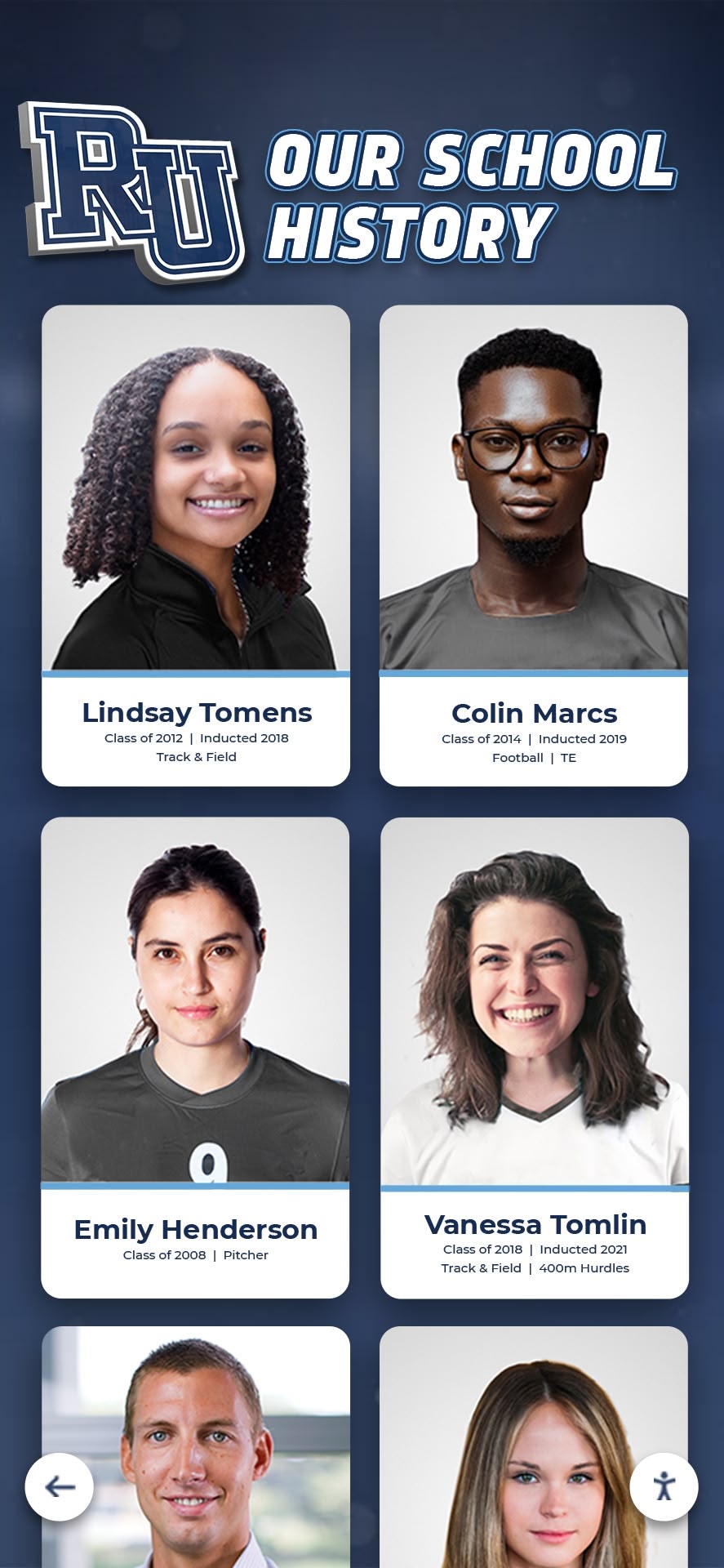

Digital recognition solutions like those offered by Rocket Alumni Solutions provide particularly effective approaches for consolidated schools. These platforms can showcase unlimited inductees from multiple predecessor schools, organize recognition by historical institution, and provide rich multimedia storytelling that brings merged school histories to life for current students unfamiliar with those traditions.

Creating Unified Identity While Honoring Diversity

Consolidated schools must balance celebrating merged school histories with building cohesive new institutional cultures:

Inclusive Governance: Ensuring representation from all merged communities in school boards, advisory committees, and decision-making processes.

Shared New Traditions: Creating new traditions, ceremonies, and celebrations that belong equally to all students rather than favoring one predecessor school.

Equitable Facility Use: Rotating significant events and activities across facilities from different merged communities when multiple buildings remain operational.

Cross-Community Activities: Programming that deliberately connects students and families from different merged communities, building relationships across traditional boundaries.

Unified Vision: Articulating shared values and aspirations that transcend predecessor school identities while respecting their importance.

Schools that successfully navigate this balance create strong unified cultures while maintaining connections to important community histories. School historical timeline displays can visually communicate these complex merged narratives, helping students understand their school’s evolution.

Lessons from School Consolidation History

The century-long school consolidation story offers important lessons for contemporary education policy and practice:

Efficiency Doesn’t Equal Effectiveness

The consolidation experience demonstrates that administrative efficiency and educational effectiveness don’t always align. While consolidation reduced the number of school districts dramatically and lowered some costs, the educational benefits proved less clear-cut than advocates predicted. Policy makers should carefully distinguish between efficiency gains and actual improvements in learning outcomes.

Community Matters in Education

The intense resistance consolidation triggered reveals how deeply communities value local schools beyond their educational function. Schools serve as community anchors, identity sources, and democratic institutions. Education policy that ignores these community dimensions may achieve technical objectives while inflicting significant social costs.

Context Determines Optimal Approaches

The small schools movement’s urban success while rural consolidation continues highlights how context shapes what works educationally. Solutions effective in one setting may prove inappropriate elsewhere. Education policy should allow flexibility for local conditions rather than imposing uniform approaches.

Change Creates Winners and Losers

Consolidation benefited some students by providing access to enhanced resources and opportunities while disadvantaging others through lost community connections, longer commutes, and reduced local control. Honest policy-making acknowledges these tradeoffs rather than presenting changes as universally beneficial.

Heritage and Identity Require Intentional Preservation

When institutions merge, the heritage of predecessor organizations can easily disappear without deliberate preservation efforts. Consolidated schools that thrive invest in maintaining connections to merged school histories, recognizing that these traditions matter to alumni, communities, and institutional identity.

Modern tools for preserving school history enable consolidated schools to maintain comprehensive archives of merged institutions while making this heritage accessible to current students who may have no direct connection to predecessor schools.

The Role of Technology in Modern School Heritage

Contemporary consolidated schools leverage technology to address historical preservation challenges in ways previous generations couldn’t access:

Digital Archives and Accessible History

Modern digital platforms transform how schools preserve and share institutional heritage:

Comprehensive Documentation: Digital archiving solutions enable schools to preserve thousands of photographs, documents, and artifacts from merged institutions without physical storage constraints.

Searchable Databases: Digital systems allow students, alumni, and community members to easily explore specific time periods, individuals, achievements, or events from any predecessor school.

Multimedia Storytelling: Video interviews with alumni, historical photographs, newspaper articles, and oral histories create rich narratives that bring merged school histories to life.

Remote Access: Web-accessible platforms extend heritage preservation beyond physical school buildings, connecting distant alumni with their alma maters regardless of geographic location.

Interactive Exploration: Touchscreen displays in school lobbies enable students to interactively explore merged school histories, discovering connections to current programs and traditions.

Honoring All Traditions Equitably

Digital recognition platforms address a persistent challenge in consolidated schools—how to honor multiple predecessor institutions fairly within limited physical space:

Unlimited Capacity: Unlike traditional trophy cases or plaque walls that favor certain schools due to space constraints, digital systems can showcase unlimited achievements from all merged institutions equally.

Organized Presentation: Sophisticated filtering allows users to explore recognition by predecessor school, time period, achievement type, or unified institutional timeline.

Balanced Representation: Administrative oversight ensures equitable representation of all merged schools rather than inadvertently privileging certain traditions.

Evolving Recognition: Digital systems grow naturally as new achievements occur and historical discoveries emerge, unlike static physical displays that become outdated.

Schools implementing comprehensive digital recognition often report improved community satisfaction as alumni from all predecessor schools see their traditions honored appropriately. These systems become unifying elements that respect diversity while building shared institutional pride.

Supporting Alumni Engagement Across Generations

Consolidated schools face unique alumni engagement challenges as they maintain relationships with graduates from multiple predecessor institutions spanning different eras:

Multi-Institutional Navigation: Alumni directory systems organized by both predecessor school and graduation year help alumni find classmates and reconnect across merged communities.

Targeted Communications: Digital platforms enable communications tailored to specific predecessor schools, graduation years, or interest areas, making outreach more relevant.

Virtual Reunions: Online platforms facilitate connections among geographically dispersed alumni from schools that may have closed decades ago.

Shared Celebration: Digital recognition visible to all alumni—regardless of which predecessor school they attended—builds appreciation for the broader institutional community.

These technological approaches help consolidated schools maintain strong relationships with diverse alumni populations who may initially identify primarily with their original schools rather than the merged institution.

Financial Realities and Long-Term Sustainability

The economic dimensions of school consolidation extend beyond initial merger decisions to long-term operational sustainability and resource allocation.

True Costs of Consolidation

While consolidation advocates emphasized cost savings, complete economic analysis reveals complex financial realities:

Transportation Costs: Consolidated schools often spend substantially more on transportation than predecessor small schools required. Long bus routes, large fleets, fuel costs, and driver salaries represent significant ongoing expenses.

Capital Investment: Building new consolidated schools requires substantial upfront investment. Many consolidated schools carry bond debt for decades after construction.

Facility Maintenance: Larger buildings cost more to heat, cool, clean, and maintain than multiple smaller structures, though per-square-foot costs may decrease.

Administrative Expansion: Consolidated districts often develop larger administrative bureaucracies, increasing overhead that may offset instructional cost savings.

Deferred Maintenance: Some consolidated schools absorbed deteriorating buildings from merged districts, inheriting substantial maintenance backlogs requiring expensive remediation.

Honest financial analysis considers these full lifecycle costs rather than only comparing per-pupil instructional expenses, revealing more nuanced cost-benefit calculations than early consolidation advocates acknowledged.

Funding Rural Education in Consolidated Systems

Consolidated rural schools continue facing financial challenges despite mergers:

Transportation Geography: Students in sparsely populated areas travel long distances regardless of consolidation, creating transportation costs that urban districts don’t face.

Enrollment Declines: Continued rural depopulation reduces enrollment in consolidated schools, increasing per-pupil costs as fixed expenses spread across fewer students.

State Funding Formulas: State funding systems often disadvantage rural consolidated districts through formulas favoring larger enrollment or failing to adequately compensate for transportation and facility costs.

Local Tax Base Limitations: Rural areas generally have smaller tax bases than suburban or urban districts, constraining local revenue even after consolidation.

Specialized Service Provision: Rural consolidated schools struggle providing specialized services like advanced courses or special education programs due to smaller student populations despite consolidation.

These persistent financial pressures mean that consolidation, while addressing some efficiency concerns, didn’t permanently solve rural education funding challenges.

The Future of Consolidated Schools

As consolidated schools look toward the future, they navigate ongoing demographic, technological, and educational changes while maintaining connections to their complex histories.

Demographic Shifts and Adaptation

Consolidated schools must adapt to continuing demographic evolution:

Rural Depopulation: Many rural areas continue losing population, creating pressure for additional consolidation or alternative educational models like online learning supplementing small physical schools.

Changing Agricultural Economy: Modern agriculture requires fewer workers, reducing rural employment and population that originally sustained both small schools and many consolidated institutions.

Economic Development: Some consolidated schools anchor rural economic development efforts, with school quality influencing business location and family relocation decisions.

Immigrant Communities: In some rural regions, immigrant populations bring demographic growth and cultural diversity, challenging consolidated schools to serve increasingly varied communities.

Remote Work Opportunities: Emerging remote work patterns may enable some rural population stabilization if consolidated schools offer education quality attracting remote workers with families.

These demographic forces will continue shaping consolidated school evolution, potentially triggering further restructuring in some regions while creating unexpected growth opportunities in others.

Educational Innovation and Technology

Technology creates new possibilities for addressing historical consolidation tradeoffs:

Blended Learning: Digital curriculum can provide small schools access to advanced courses without requiring specialized teachers physically present, potentially supporting smaller schools’ educational viability.

Virtual Athletics and Activities: Online competitions, performances, and collaborations enable smaller schools to offer extracurricular experiences despite limited local participation numbers.

Community Connections: Technology allows schools to maintain stronger connections with distant alumni and community members, addressing community fragmentation consolidation sometimes created.

Personalized Learning: Digital platforms enable personalized instruction adapting to individual student needs, potentially addressing small school limitation of limited peer numbers while retaining personalization advantages.

Heritage Preservation: As discussed previously, digital recognition and archiving technologies help consolidated schools preserve and celebrate merged school histories more comprehensively than physical displays alone permit.

These technological capabilities don’t negate consolidation tradeoffs but provide tools for managing them more effectively while honoring institutional complexity.

Policy Considerations Moving Forward

Contemporary education policy makers can learn from consolidation history when addressing today’s rural education challenges:

Flexibility Over Uniformity: Rather than mandating consolidation or specific school sizes, policies might support diverse local solutions appropriate to particular contexts and communities.

Adequate Funding: Rural school funding formulas should recognize genuine cost differences—particularly transportation and specialized service provision—rather than penalizing sparsely populated areas.

Technology Investment: Supporting technology infrastructure and digital learning platforms in rural areas can provide educational breadth without necessarily requiring physical consolidation.

Community Engagement: Policy changes affecting schools should involve meaningful community input, recognizing that schools serve functions beyond academic instruction.

Heritage Preservation: When consolidation does occur, providing resources and support for heritage preservation helps communities maintain connections to their educational traditions.

Thoughtful policy informed by consolidation’s complex history can better balance efficiency, educational quality, and community needs than approaches focusing narrowly on administrative rationalization.

Celebrating Merged School Heritage Today

For consolidated schools currently operating, celebrating all predecessor school legacies while building unified identity remains an ongoing process requiring intentional effort and appropriate tools.

Creating Comprehensive Recognition Programs

Effective consolidated school recognition programs acknowledge and honor achievements across all merged institutions:

Historical Research: Documenting achievements, traditions, and notable alumni from all predecessor schools provides foundation for comprehensive recognition.

Inclusive Selection: Hall of fame committees representing all merged communities ensure balanced recognition rather than inadvertently favoring certain predecessor schools.

Multi-Era Celebration: Recognition programs spanning from predecessor schools’ earliest years through the present demonstrate institutional continuity while honoring change.

Community Collaboration: Engaging alumni associations, local historical societies, and community members from all merged areas in heritage preservation efforts.

Physical and Digital Platforms: Combining traditional recognition elements with modern digital systems creates comprehensive programs accessible to diverse audiences.

Solutions like digital halls of fame particularly suit consolidated schools because they can organize content by predecessor institution, allow unlimited honorees from all merged schools, and provide rich context explaining institutional evolution and merged traditions.

Annual Heritage Events and Celebrations

Many consolidated schools create annual traditions explicitly honoring their merged heritage:

Founder’s Day Celebrations: Events recognizing founding of predecessor schools and the consolidation that created the current institution.

All-School Reunions: Gatherings welcoming alumni from all predecessor schools and all eras, building connections across traditionally separate groups.

Heritage Weeks: School-wide programming exploring history of merged schools, featuring alumni speakers, historical displays, and educational activities.

Athletic Heritage Nights: Sporting events honoring athletic traditions from all merged schools, with special recognition for athletes from predecessor institutions.

Historical Exhibitions: Rotating displays featuring photographs, memorabilia, and stories from different predecessor schools, ensuring all traditions receive attention.

These traditions help current students understand their school’s complex history while providing alumni from merged schools opportunities to maintain connections with their heritage.

Engaging Alumni Across Merged Communities

Consolidated schools with strong alumni engagement typically implement strategies that honor all predecessor school identities:

Inclusive Communications: Publications and digital communications acknowledge all merged schools, using language and imagery representing the full institutional family.

Predecessor School Networks: Supporting alumni chapters organized around predecessor schools while connecting them to the broader consolidated school community.

Giving Campaigns: Fundraising efforts that allow alumni to designate gifts to specific predecessor school scholarships or programs while supporting overall institutional needs.

Mentorship Programs: Alumni mentorship initiatives connecting current students with alumni from all merged schools, building intergenerational and cross-community relationships.

Recognition Equity: Ensuring alumni from all predecessor schools receive fair consideration for awards, hall of fame induction, and institutional recognition.

When consolidated schools demonstrate genuine respect for all merged school traditions, they build stronger unified communities that honor diversity while moving forward together.

Conclusion: Honoring the Past While Building the Future

The history of school consolidation in America represents a complex story of educational transformation, economic necessity, community disruption, and institutional reinvention. Over the past century, the consolidation movement fundamentally restructured how rural Americans experience education, replacing thousands of small community schools with larger, more comprehensive institutions.

This transformation delivered genuine benefits—increased curriculum breadth, specialized instruction, advanced facilities, and economic efficiencies. However, it also imposed real costs including lost community cohesion, reduced local control, and disrupted traditions. The consolidation experience demonstrates that educational policy involves value judgments and tradeoffs rather than simply technical optimization.

For the thousands of consolidated schools operating today, the challenge lies in honoring the distinct traditions and achievements of merged predecessor institutions while building unified school cultures serving current students. This requires intentional effort, appropriate resources, and recognition that heritage preservation matters to community identity and institutional strength.

Modern digital recognition platforms provide particularly effective tools for meeting this challenge. Unlike physical trophy cases or plaque walls with limited space that must choose which traditions to highlight, comprehensive digital systems can showcase unlimited achievements from all merged schools, organize content by predecessor institution, and provide rich multimedia storytelling that brings merged histories to life.

The schools that thrive in the 21st century will be those that learn from consolidation’s complex history—understanding that efficiency and community, progress and tradition, unity and diversity need not be opposing values but can be balanced through thoughtful policies, inclusive practices, and recognition approaches that celebrate institutional complexity rather than oversimplifying it.

For consolidated schools seeking to honor all merged school traditions while building strong unified identities, comprehensive digital recognition solutions offer powerful tools. Explore how Rocket Alumni Solutions can help your consolidated school celebrate achievements from all predecessor institutions, create accessible digital archives, and build recognition programs that unite your community while respecting its diverse heritage.